Litecoin

Grade: E

Summary

Litecoin was designed in 2011 as a lighter and faster version of Bitcoin, using a modified proof-of-work consensus mechanism. It was the first altcoin created and aims to provide faster transaction confirmation times.

Litecoin succeeded with this goal and remains one of the most popular cryptoassets, never dropping from the top 20 since inception. However, we identify several drawbacks, namely the inability to compete with proof-of-stake blockchains. Mining is a slower method of transaction validation which has hindered the number of users and developers operating on Litecoin. Ultimately, this degrades utility, and we suggest it will fail to compete over time.

| Pillar | Grade |

|---|---|

| Financial Prospects of the Network | D |

| Network and Usage | E |

| Comparison with Traditional Finance Alternatives | D |

| Future Utility | E |

| Weighted Grade | E |

I. Financial Prospects of the Network

Tokenomics

Litecoin is a Layer-1 blockchain. Its native currency – LTC – is capped at 84mm tokens, but not all are in circulation. Rather, like Bitcoin, Litecoin uses proof-of-work (PoW) consensus to release new coins with each block. PoW demands that network nodes validate transactions and add new blocks to the blockchain in a process called mining. For their work, miner nodes are rewarded with newly generated LTC. In theory, miners could indefinitely mint LTC and inflate its price, so Litecoin implements halving to control supply, cutting the rewards a miner receives for adding new blocks at regular intervals. In Litecoin’s case, halving occurs every 840,000 transactions, with the next event expected in 2027. At launch, rewards were 50 LTC, but are now 6.25 LTC.

Halving mediates inflation, since miners work harder for diminishing rewards. Consider that current rewards generate US$378 per block; the next halving will reduce this to US$189 if current price (US$60.45) stands. Logically, the more resource required to obtain an asset, the more value it holds, and we may expect LTC to appreciate over time. In theory, to retain US$378, LTC must appreciate to US$120 following halving.

LTC is a unit of currency, offering similar characteristics to bitcoin in support of peer-to-peer payments. One LTC is divisible as far as one photon – 0.00000001 LTC. It is digital, portable and secure in a user’s digital wallet. It is fungible, transferable and exchangeable for goods on the Litecoin network.

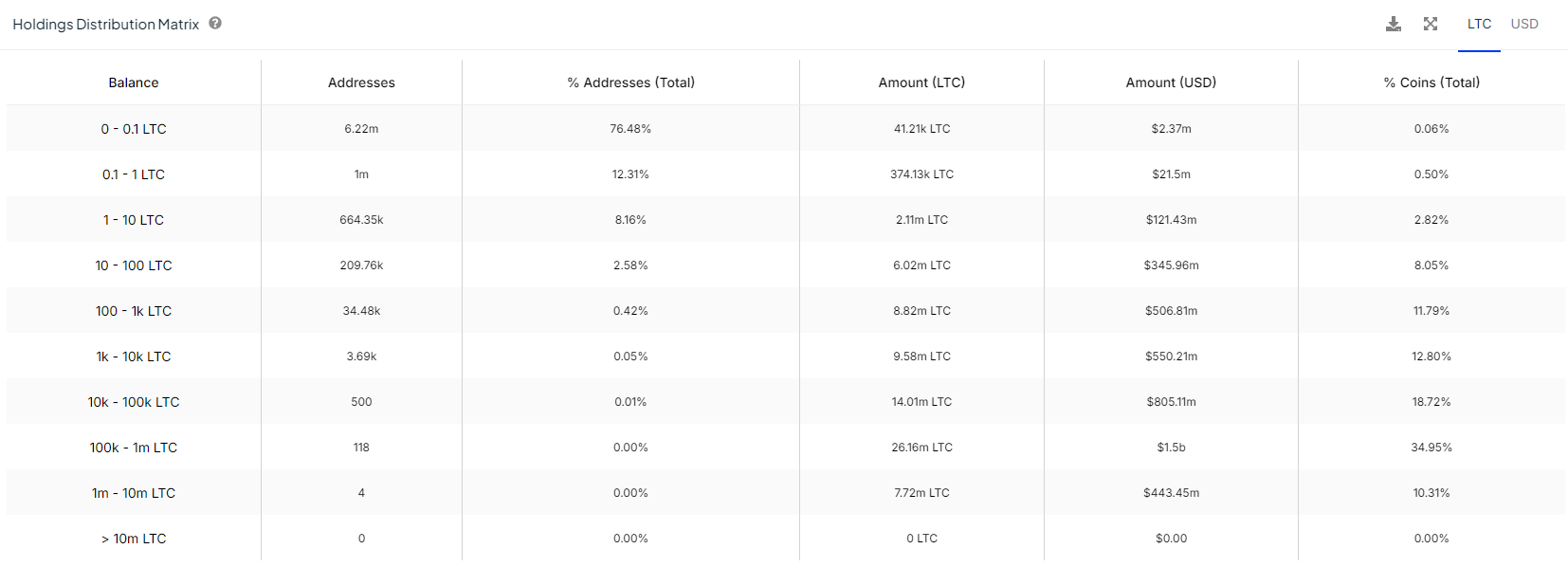

74,841,775 LTC are in circulation, 89.1% of maximum supply. At a market price of US$60.47 per token, Litecoin has a market cap of US$4,525,393,861 – 19th highest of all cryptoassets. Typically, higher circulating totals indicate greater decentralisation of token distribution. We review ownership to determine whether this is the case.

Distribution appears balanced. Retail users hold 51.7% of tokens, whales 10.31% and institutional investors hold the remainder. Retail ownership sits in the median of all tokens we have analysed: retail investors hold 88.11% of BTC, 48.56% of ETH, 71.35% of ADA and 31.66% of ALGO. However, the top 122 wallets own 45.26% of all tokens and US$1.94bn in value (whales: 1mm-10mm tokens). This consolidates a large proportion of LTC tokens with a few institutional investors, presenting risk to smaller investors who are exposed to unpredictable price moves.

Revenue Streams

Blockchain networks that cap their total supply must find a way to sustain themselves in the long term. Once all coins are minted, unless networks incentivise miners, no one will validate transactions and the blockchain will become redundant. So, networks require users to pay fees when they transact. With Litecoin, users can expect to pay U$0.004 per transaction, whereas Bitcoin charges around U$1.1. Litecoin has lower fees because it allocates a portion of total supply to miners, incentivising them with a separate pool. It does not rely solely on fees.

Fees indicate how much users will pay to use the blockchain and we can compare competitors to estimate value. Litecoin generates low fees, annualised at US$4.53mm, in-part attributable to its low charging model. Bitcoin generates US$251.85mm, implying more transactions are undertaken on Litecoin. However, Litecoin derives a price-to-fee (PF) ratio of 14,645, meaning its fair value is currently 14,645x higher than the economic value it captures. Bitcoin’s is 4,763x, suggesting its market cap is more appropriate based on its fundamentals. However, both are outsized and indicate serious overvaluation. Litecoin also generates fewer fees than Dogecoin, despite the latter a meme coin. None of the three PoW blockchains book revenue.

| Network | Fees (L30D, USD) | Fees (annualised, USD), 30d% Change | Market Capitalisation (USD) | Price-to-Fees Multiple |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bitcoin | $20.70mm | $251.85mm (-70.7%) | $1.2tn | 4,763x |

| Dogecoin | $73.93k | $899.48k (-25.2%) | $15.29bn | 17,002x |

| Litecoin | $25.42k | $309.33k (-19.6%) | $4.53bn | 14,645x |

Date: 09 August 2024

Source: token terminal

PoW blockchains derive fewer fees than their proof-of-stake (PoS) counterparts. Filecoin, for example, with a market cap half that of Litecoin, generates US$4.57mm in fees for a PF of 477x. Ethereum records US$1.25bn and Solana US$630mm for ratios of 255 and 117, respectively. This strongly suggests that users find more utility in PoS networks, to the detriment of PoW. We suggest Litecoin cannot sustain itself if it does not consider its consensus mechanism.

Financial Metrics

Total Value Locked (TVL) on Litecoin stands at US$3.1mm, which is extremely low. Bitcoin, for example, has US$646mm; other Layer-1 blockchains such as TRON and Solana host US$7.71bn and US$4.98bn, respectively. TVL is crucial, revealing the sum of capital inflow from users, and higher sums indicate greater trust in the blockchain. It is correlated with both value and utility, but Litecoin’s market cap is 1,466x greater than locked capital. A ratio of 1.0 is considered healthy. Litecoin has failed to capture even US$10mm in the last year, spiking to just US$7.36mm in March. Users do not support its utility.

We map price, volume and volatility of LTC over the last 90 days, observing a 36.7% price decline between 21 May and 5 August and volatility prevalent in July. The market declined too, with total crypto capitalisation dropping 26.7% across the period, but Litecoin experienced a more severe downturn. On average, 405,060 LTC are traded each day, contributing to an average daily value of US$30.37mm traded. This is substantially lower than other tokens (see Filecoin, Ethereum and Bitcoin), indicating LTC is less popular with users and investors.

Date: 09 August 2024

Source: Investing.com

II. Network and Usage

Network Metrics

Litecoin spawned from a copy of Bitcoin’s code in 2011, with changes implemented on the new version. The two are extremely similar, but Litecoin sought to address Bitcoin’s scaling limitations. Principally, Litecoin implemented a new hashing algorithm – Scrypt – to support faster transaction speeds. Bitcoin uses SHA-256 and processes around 7 per second to generate new blocks every 10 minutes. Litecoin processes 56 transactions per second and creates new blocks every 2.5 minutes. Transactions are four times faster and it can be argued that Litecoin is better for daily transactions. However, Bitcoin currently supports 3.44mm transactions per day, to Litecoin’s 1.82mm. Both support block sizes of around 1MB (1,500 transactions), which means Bitcoin is used at nearly double the rate of Litecoin, despite slower processing.

Litecoin was created to improve on Bitcoin, but does not process as many transactions, suggesting users find lower utility. It fails to adequately position itself as a better alternative. More damning is the fact that PoS networks offer significantly faster processing than either – Cardano can support 386 transactions per second and Algorand 3,227. It is further evidence that PoW networks suffer a lack of long-term utility compared with more agile PoS counterparts.

User Adoption

People interacting on blockchain networks can be broadly split into two camps: service users and developers. Litecoin’s service user base has increased 31.95% over the past year: 484,010 addresses were registered at the end of July 2023, rising to 638,660 across the year. Active addresses – those interacting on-chain daily – have increased 35.47% to 310,760. The network is growing. However, despite this, Litecoin fails to attract as many users as its competitors.

| Blockchain | Total Addresses | Daily Active Addresses |

|---|---|---|

| Bitcoin | 1,320,000 | 705,210 |

| Cardano | 43,950 | 26,910 |

| Dogecoin | 70,080 | 42,460 |

| Ethereum | 740,790 | 530,910 |

| Litecoin | 638,660 | 310,760 |

| Tron | 2,630,000 | 2,260,000 |

Date: 26 July 2024

Source: IntoTheBlock

This is important because users stimulate economic activity and give value (fees) back to miners and developers in the ecosystem. Yet, developers are not hugely attracted to Litecoin either. 81 developers built on the ecosystem in July 2024, down 11% year-on-year, of which just 33 operated full time. Bitcoin attracted 1,246 developers, down 7% year-on-year, but research reveals that developers are more attracted to PoS layers.

This is further evidence that PoW blockchains have faltering utility. Developers build decentralised applications (dApps) on blockchains to support network growth and, in theory, more developers will support productivity and value production. In a virtuous cycle, users frequent environments that offer more utility, increasing fees and encouraging more entrepreneurs to operate innovative dApp functionalities. Low developer numbers suggest Litecoin is not attractive for experimentation, which will likely diminish its long-term utility.

Smart Contracts and dApps

As a direct descendant of Bitcoin, Litecoin is a testing ground for many of Bitcoin’s upgrades. For example, the Lightning Network was first trialled on Litecoin, as was the Segregated Witness upgrade. Because they share the same underlying technology, Litecoin can test errors in an environment where failures would cause less damage.

However, Litecoin was not designed to host smart contracts or dApps, which makes it hard to build on. Both innovations are key for economic value creation. Consider the tools available in decentralised finance (DeFi) that automate insurance settlement, bet settlement, market making, yield generation and more – functionalities that attract users. Ethereum and Solana pioneer smart contracts and are market-leading networks. Litecoin, without either, could struggle to sustain relevance against more advanced blockchains.

Instead, Litecoin positions itself for low cost, quick payments, which it achieves. But we consider the long-term utility of blockchain networks; without smart contracts or dApps, Litecoin offers less utility.

III. Comparison with Traditional Finance Alternatives

Cost-Benefit Analysis

A frequent argument against blockchain technology raises its environmental impact. PoW consumes a lot of energy, as mathematical computations increase in difficulty and require greater hash rates to solve. Mining pools need energy to run and water to cool.

Bitcoin is particularly hungry, with studies suggesting it consumes 100-200 terawatt hours (TWh) per annum – as much as, or more than, nearly 200 individual countries. Litecoin also deploys PoW and consumes 18.5 kWh per transaction, to Bitcoin’s 707. It is more efficient, but still disproportionate to what it achieves. Visa processes 1,700 transactions per second at an average of just 1.5-watt hours per transaction. Both Bitcoin and Litecoin struggle to justify their operations in this context.

Market sentiment is moving towards greener digital currencies. Ethereum, for example, changed its consensus mechanism from PoW to PoS, in part for increased sustainability. Algorand, Ripple and Cardano also focus on sustainable deployment. Again, we see evidence that Litecoin’s mechanism degrades its long-term utility. It is not justifiable to mine when cheaper, faster and more sustainable alternatives exist.

Security and Trust

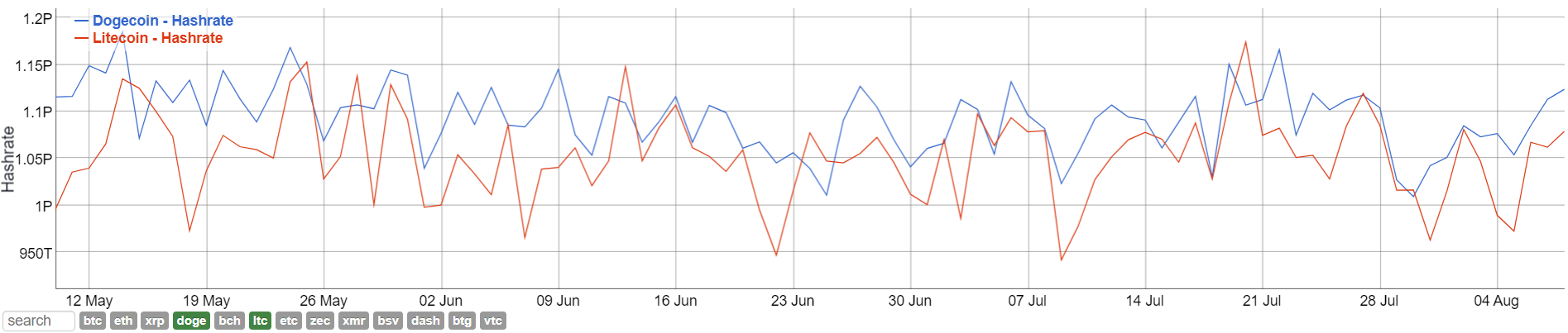

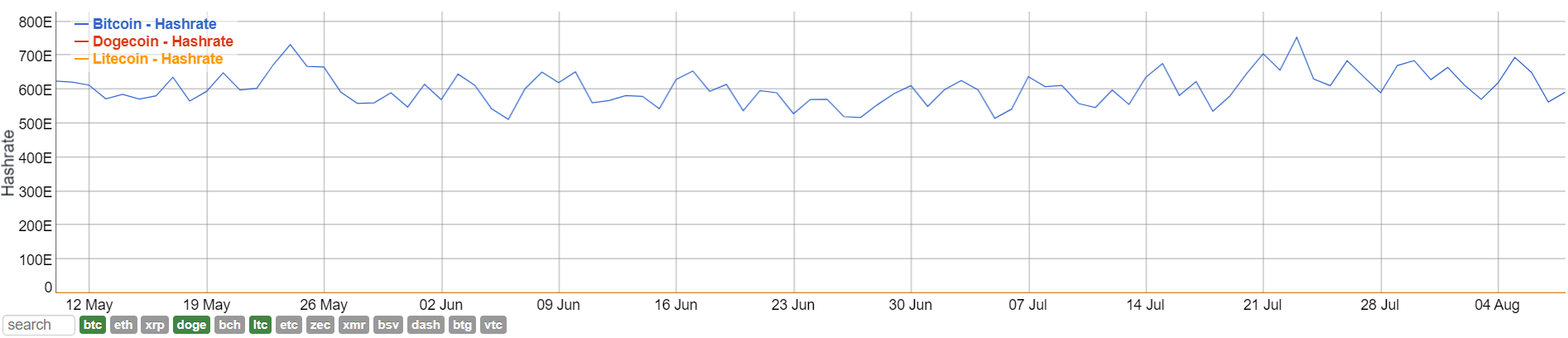

Hash rate measures the computational power of PoW networks and determines the difficulty to mine a block. A hash is a randomly generated alphanumeric code, and miners guess that code by piling computational resource into calculations. Each guess submitted by nodes is measured, calculating a hash rate per second. This metric is important as it indicates the difficulty for a bad actor to hack the network. A Sybil attack, in which an attacker gains 51% of a network’s power, is easier when there are fewer miners. Decentralisation is, therefore, integral to security, since more hash power makes it more costly for a hacker to gain control.

Litecoin and Dogecoin both oversee hash rates above 1 Peta hash per second, on average. This means 1 quadrillion hashes per second, indicative of a large mining pool. That said, Litecoin is far less secure than Bitcoin, which hosts roughly 600 Exa hashes per second (1 quintillion hashes). In theory, it would be easier to hack Litecoin than Bitcoin, though, in practice, neither are likely. Litecoin is very secure.

Its security is also dependent on price. If LTC falls, mining rewards shrink, which may discourage miners and support less hashing power. Given this, it is imperative that Litecoin supports its long-term future.

Date: 09 August 2024

Source: BitInfoCharts

Date: 09 August 2024

Source: BitInfoCharts

Accessibility and Inclusivity

As a Layer-1 network, Litecoin supports near instant, low-cost peer-to-peer payments between anyone in the world. In practice, this means that buyers and sellers from different continents can transact without needing to trust one another. Litecoin is also open source, released under the MIT/X11 license, allowing anyone to run, modify, copy and distribute the software. This supports transparent and independent verification of source code to attract users to a safe, auditable environment.

The goal of blockchain is to achieve decentralisation. As above, PoW networks rely on miners to validate transactions, and miners ought to be decentralised to prevent one actor controlling the hash rate. But, with any given bull run in the crypto market, mining rewards increase, and mining pools vie to win blocks for payment. Miners are incentivised to deploy more computational resource which can lead to a dangerous scenario whereby hash power is concentrated. Specifically:

- One company controls pools totalling >50% of network hash power

- One company controls machines totalling >50% of network hash power

We covered this scenario in our analysis of Bitcoin. It is estimated that the right set up would allow a beginner to mine 1 LTC in 45 days, whereas institutional miners have developed their own Application-Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC) machines for mining. Centralisation is a risk, since market leaders (Litecoinpool.org, F2Pool, Antpool, Poolin and ViaBTC) deploy so much power that, over time, it becomes unfeasible for smaller miners to partake. The landscape has become much less competitive and now centres around a small set of pools.

IV. Future Utility

Roadmap and Development

Litecoin’s founder, Charlie Lee, was an ex-Google and Coinbase employee. He famously sold his entire LTC position during the 2017 bull run but remains active in the community. Litecoin does not have a formal governance system, relying instead on off-chain consensus. Protocol changes are enacted by the Core Development Team, a subset of the Litecoin Foundation headed by Lee. Funds to support development are acquired by donations from just eight individuals, four of whom are on the Foundation Board. Our view is that this hinders the decentralisation and diversity of idea generation, which may hurt Litecoin’s prospects.

Unlike other Layer-1s, Litecoin does not publish a roadmap in aggressive pursuit of Ethereum’s market share. Rather, the protocol aims to fulfil its role as a low-cost alternative to Bitcoin. For success, then, Litecoin needs more merchants accepting LTC and more people using it as cash. Accordingly, developers are improving wallet and merchant software, for example with work on P2P support, wallet address support, view key support and payment proofs. Additionally, MimbleWimble protocol launched on top of Litecoin to encrypt transaction details, improving privacy for users.

Litecoin is committed to payments support. It is accepted by many payment service providers, with the full list available here.

Risks and Mitigations

Litecoin’s use case is vulnerable as it cannot match the security of Bitcoin, nor is it perceived as great a store of value. If Bitcoin successfully solves its scaling issues, Litecoin’s value proposition as a faster, cheaper alternative would be eroded. And Bitcoin has moved to rectify its scalability. The Lightning Network, running alongside Bitcoin, enables near-instant settlement for transactions. Though the Lightning Network has not levelled the playing field between Bitcoin and Ethereum, it addresses certain constraints. Further development would reduce the need for Litecoin as a faster alternative.

Additionally, an array of networks offer faster transaction completion than Litecoin, further intensifying competition. It does not hold pole position for fast and low-cost transactions, nor does it provision transaction settlement sustainably. What, then, is Litecoin’s value-add?

Relevance

Litecoin is one of the oldest and most well-known cryptoassets in the market, retaining popularity among investors. It is listed on many exchanges, bought and sold with ease and has remained in the top 20 cryptoassets by market cap since inception. Litecoin sought to differentiate itself from Bitcoin by applying a different hashing function and succeeded in supporting more transactions per second than its predecessor. In addition, it supports microtransactions at a much cheaper rate than Ethereum and Bitcoin, which is attractive for users.

However, analysis reveals serious drawbacks. PoW consensus greatly hinders Litecoin, subduing the number of developers and users attracted to the network. PoS blockchains offer faster transactions than Litecoin, which reduces the utility of its key differentiator to Bitcoin.

Litecoin will struggle if this does not change. Whether it has the bandwidth, time or willingness to redeploy as a PoS is a different story. Litecoin does not differentiate itself, rather, it remains a copycat of Bitcoin that fails to compete with more agile competition. And mining is costly, has poor environmental impacts and is subject to centralisation within a small pool of participants.

We view Litecoin’s long-term prospects negatively. It does not offer distinguishable value to users.

Disclaimer: This analysis is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice. Readers are encouraged to conduct their own research and seek professional advice before making investment decisions.

References

Aggarwal, S., & Kumar, N. (2021). Chapter Twelve – Cryptocurrencies. Advances in Computers, 121, 227-266.

Anderson, S. (2023). Segregated Witness (SegWit): Definition. Available at: Investopedia (Accessed: 10 August 2024).

Becher, B. (2023). What Is Litecoin?Available at: Built In (Accessed: 10 August 2024).

Blockchain Bytes. (2024). Riding the Bull: Unveiling the Top Litecoin Mining Pools of the Season. Available at: Medium (Accessed: 10 August 2024).

Brooke, C. (2024). The Beginner’s Guide to Litecoin Mining. Available at: 99 Bitcoins (Accessed: 10 August 2024).

Brosens, T. (2017). Why Bitcoin transactions are more expensive than you think. Available at: ING (Accessed: 10 August 2024).

CoinWire. (2024). Everything You Should Know About Investing in Litecoin. Available at: CoinWire (Accessed: 10 August 2024).

Digiconomist. (2023). Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index. Available at: Digiconomist (Accessed: 10 August 2024)

Dwyer, K. (2022). Litecoin vs. Bitcoin. Available at: CoinMarketCap (Accessed: 09 August 2024).

Electric Capital. Developer Data. Available at: https://www.developerreport.com/.

Filcak, R., Povazan, R., & Viaud, V. (2020). Blockchain and the environment. Available at: European Environment Agency (Accessed: 10 August 2024).

Hillard, D. (2021). Litecoin Core Report. Available at Crypto EQ (Accessed: 09 August 2024).

Napoletano, E., & Powell, F. (2024). What Is Litecoin? How Does It Work? Available at: Forbes (Accessed: 09 August 2024).

Radmilac, A. (2023). The centralisation of Bitcoin: Behind the two mining polls controlling 51% of the global hash rate. Available at: CryptoSlate (Accessed: 18 April 2024).

Song, J. (2018). Mining Centralization Scenarios. Available at: Medium (Accessed: 10 August 2024).

van den Boogaard, A. (2022). Litecoin: everything you need to know about LTC. Available at: Blox (Accessed: 09 August 2024).

Vega, M. A. G. (2023). The high energy cost of the cryptocurrency race. Available at: Cepsa (Accessed: 10 August 2024).

Wade, J. (2023). Hash Rate: How It Works and How to Measure. Available at: Investopedia (Accessed: 09 August 2024).

Leave a comment