Unlocking Opportunities

The Rise of Cryptoasset Trading Among Retail Investors

Date

March 2024

Author

Charlie Kellaway

Reading Time

13 minutes

Retail Participation in Financial Markets

Retail trading has boomed in recent years, with individual investors increasingly playing a significant role in global financial markets. Europe has witnessed a recovery in retail ownership since the 2008 financial crisis: households now own 15.6% of listed shares in Europe and the United Kingdom (UK), up from 13.3% in 2013 [1]. There has also been sustained growth in activity since the turn of the decade. In-part accelerated by COVID-19, considerable volumes were traded during six weeks of high volatility between February and March 2020, when people were stuck at home with greater disposable income. For example, in the United States (US), monthly retail activity more than doubled in March 2020 alone and retail trading accounted for 23% of all equity trading activity that year [2]. European countries also observed higher levels of participation as volumes nearly quadrupled in Spain and Germany [3].

Though most transactions originated with existing investors, a significant proportion of trading was carried out by new investors and retail interest in financial markets has not faded since. Rather, retail have continued to trade at a higher rate and the number of transactions has remained above pre-COVID levels. For example, in France, the number of active retail investors has held steady at 2.5m – double the number prior to 2020 [4]. This is attributable to several factors, including growing numbers of young investors and increasing availability of financial education. But the primary driver has been technological advancement, as applications and social networks democratise access to markets. The clientele of neo-brokers – digital financial services for investing – is significantly younger than other categories of intermediaries such as traditional and online banks [5].

User-friendly platforms, mobile apps and online exchanges have lowered barriers to entry, enabling individuals to trade financial instruments with ease. Cryptoassets have gained traction, attracting a growing number of young investors seeking alternative opportunities beyond traditional assets. By mid-2022, almost 15% of individuals in the US had made transfers into crypto accounts, the majority of whom were young males, and their trading behaviour follows that unlocked by technology [6]. Cryptoasset investors trade more actively (9 vs. 2 trades per month) and log into their brokerage accounts more often (82x versus 27x per month) [7].

Technology adoption is a strong determinant of investment and its influence on young populations is extended by social media and digital communication channels [8]. For cryptoassets, digital channels have facilitated information dissemination and peer-to-peer networking, fostering a vibrant community of enthusiasts and investors. Platforms offering 24/5 trading have attempted to capture retail by capitalising on desires for increased flexibility and accessibility. Coinbase, Robinhood and eToro are examples that enable participation in crypto markets anytime, anywhere, regardless of an investor’s time zone.

Retail involvement is important because cryptoassets are not regulated, meaning investors are not protected. A paper identifying behavioural patterns of trading suggests that new users enter crypto lured by the prospect of rising prices, but upticks in user numbers lag price rises by an average of two months [9]. When crisis strikes, values can be routed, as in 2022 with the collapse of stablecoin Terra/Luna when US$450 billion of value disappeared from the market. Patterns reveal that users tried to move through the collapse by adjusting portfolios away from tokens under stress towards those with higher market capitalisations (Bitcoin, Ethereum). However, owners of large wallets – whales – reduced their holdings of Bitcoin in the days following shock episodes. Large investors likely cashed out at the expense of smaller holders, selling to retail before market declines.

As the Bank of International Settlements puts it, “In stormy seas, the whales eat the krill”.

Involvement in Crypto

To estimate retail involvement, we analyse the number of trades undertaken by global retail investors and the total volume this contributes. Volume can be defined as the total quantity of a cryptoasset traded. For example, a user may trade 10 Ether (ETH), in which case the number of trades would be one and the volume would be 10. Retail trades can be reasonably estimated by considering transactions under US$10,000. At the time of writing, ETH trades at US$3,426, so one trade of US$10,000 would have a volume of 2.92 ETH.

Chainalysis’ 2023 Global Crypto Adoption Index report considers the following [10]:

- Volume of on-chain retail value received at centralised exchanges – measuring the activity of individual cryptocurrency users based on the cryptoasset value they’re transacting.

- Volume of on-chain retail value received from DeFi protocols – measuring DeFi transaction volume carried out in retail-sized transfers.

On-chain transactions refer to trades that occur on the blockchain and are dependent on it to confirm their validity. In this environment, retail transactions constitute the lowest volumes when compared with institutional and professional investors. The report identifies that, in 2023, retail contributed between 3% (North America) and 8% (Middle East & North Africa) to global trading volumes. Considering an institutional trade of US$100,000 would purchase substantially more crypto than a trade under US$10,000, this aligns with expectations.

Retail activity shows that lower middle-income (LMI) countries display the greatest adoption. Leading countries by volumes of transactions under US$10,000 include India (1), Nigeria (2), Ukraine (3), Vietnam (4) and China (5) and a similar pattern emerges in value transferred across DeFi protocols: India (1), US (2), Vietnam (3), Nigeria (4) and Indonesia (5). The UK placed 20th and 8th, respectively.

How should we interpret this? 40% of the world’s population live in LMI countries, suggesting widespread adoption could influence the success of crypto projects. Adoption can also have a positive effect on the financial health of populations. For example, to beat rampant inflation, businesses in Venezuela convert bolívars into Bitcoin (BTC) and allow people to pay with crypto [11]. This helps the average person beat devaluations by converting pay into BTC or stablecoins (cryptoassets pegged against a stable fiat such as US$). Many LMI countries can prosper from similar uses as their domestic currency is volatile against the US dollar.

For those interested, we highly recommend reading the full report.

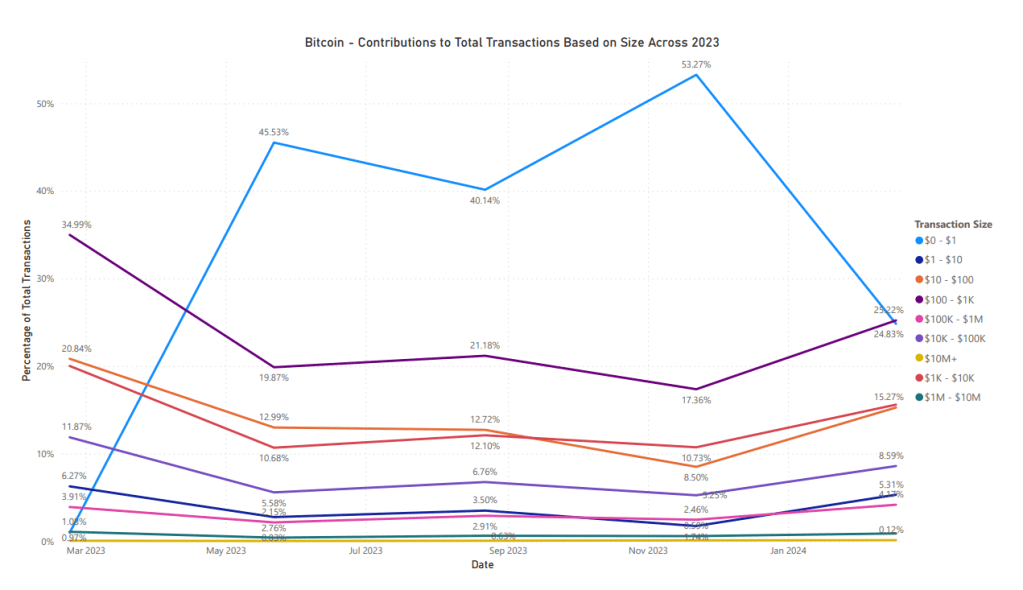

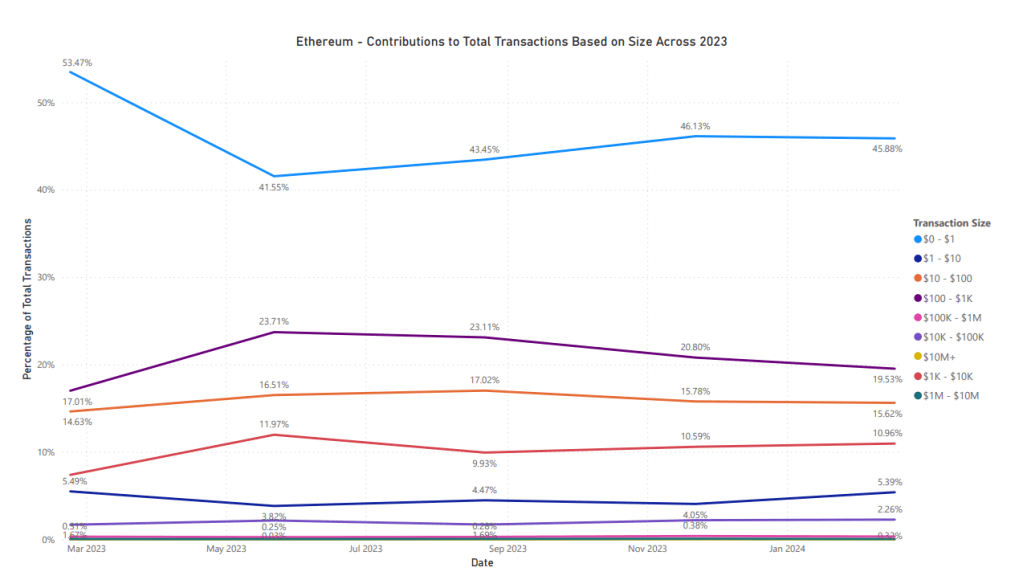

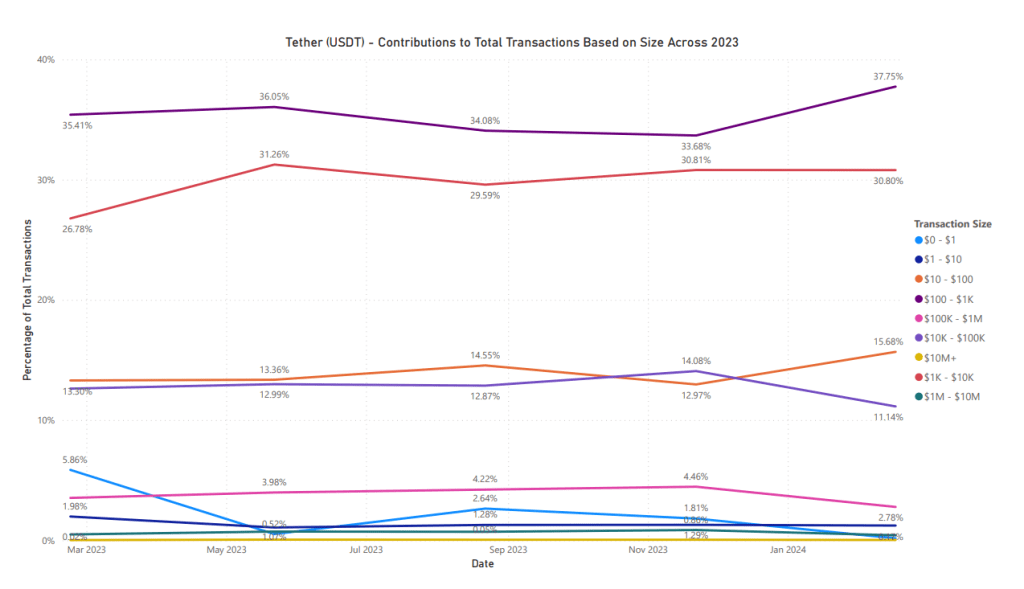

But the volume of transactions by retail users does not paint the full picture. On-chain statistics highlight transaction counts by size, so we can determine the number of transactions for a given size bracket [12]. The charts below present the number of transactions by size between February 2023-24 for the three largest cryptoassets by market capitalisation. Again, retail are broadly distinguished as transactions under US$10,000.

Source: IntoTheBlock

Source: IntoTheBlock

Source: IntoTheBlock

Figure 1 presents BTC, which has a market capitalisation of US$1.2tn, and the sheer number of retail transactions is immediately apparent. Though the number of transactions occurring at US$1-10,000 has slightly declined, the number below US$1 has leapt, currently constituting 25% of all on-chain trades. At its highest point in November 2023, transactions under US$1 formed 53.27% of all market trades.

Figure 2 shows trades for ETH, the second largest cryptoasset with a market capitalisation of US$410bn at the time of writing. The number of trades appears more constant than for BTC though, in Ethereum’s case, we observe a decline in the number of trades under US$1, from 53.47% to 45.88%. However, cumulatively, trades under US$10,000 make up 91.99% of all trades executed for ETH as of February 2024. This is far higher than BTC which, at 70.63%, appears to have significantly more institutional involvement.

Lastly, Figure 3 shows Tether (USDT), the largest stablecoin and third largest cryptoasset with a market capitalisation of US$99bn. Parallels can be drawn with BTC and ETH given retail trades constitute the largest number of transactions in USDT at 57.61%, outstripping professional and institutional by 15.22%. However, differences exist. Tether is pegged to the US dollar, meaning US$1 ≈ 1 USDT. It is perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that few trades occur under US$1 (0.17%). Professional and institutional investors have gained the largest foothold, as 11.14% of total transactions occur between US$10-100K.

Considering this, and revisiting interpretation, caution ought to be exercised. Though volumes of retail trading remain comparatively small, the data indicates that retail participate extensively in the market. If a significant proportion reside in LMI countries, it is likely that many people expose themselves to crypto without the necessary financial support navigate a crisis. And data illuminates that retail investors are swimming with far larger and more aggressive participants.

Impact

Retail enfranchisement is important, with high levels of participation contributing to well-functioning markets by improving liquidity and depth of order books [13]. The World Federation of Exchanges’ (WFE) report on enhancing liquidity noted key areas exchanges can focus on to ensure the health and vibrancy of financial markets:

- Promote the development of a diverse investor base with a focus on attracting local and international institutional investors and enhancing retail participation.

- Increase the pool of securities and associated financial products by increasing the number of local or foreign listings, launching derivative and ETF products, or creating market linkages.

- Invest in the creation of an enabling market environment through the improvement of trading technology, market and reference data, the implementation of market-maker schemes, or developing securities lending and borrowing schemes.

With the emergence of cryptoassets, financial markets are expected to adapt accordingly. In January 2024, the SEC approved several spot Bitcoin exchange-traded products (ETPs), enabling anyone – from pension funds to ordinary investors – to purchase financial instruments correlated with Bitcoin [14]. The products are expected to provide many benefits, including boosting the liquidity, transparency and efficiency of Bitcoin markets. Barriers to entry can be lowered, creating diversification opportunities to help users effectively navigate the volatility associated with cryptoassets [15].

It is needed. The rise of cryptoasset trading among retail has significant implications and reflects shifting attitudes towards existing investment paradigms. Dissatisfaction with traditional banking systems, concern about inflation and a desire for financial autonomy has prompted many young investors to explore alternatives. Additionally, the decentralised nature of blockchain technology, which underpins cryptoassets, resonates with the values of transparency, decentralisation and democratisation espoused by younger generations.

This impacts the investment behaviour and financial well-being of retail investors. One of the main reasons retail investors buy cryptoassets is their expectation of high returns. Somewhat predictably, being a male younger than 35, being from a lower middle-income country and earning less than US$20,000 annually are factors strongly correlated with crypto ownership [16]. Of course, cryptoassets are also viewed as offering diversification, a store of value and a hedge against inflation, whilst other users act on their desire to support the development of the technology and capitalise on emerging trends. However, though cryptoasset trading does present opportunities to participate in innovative financial markets and potentially generate wealth, it remains outside the regulatory scope of traditional markets and poses several challenges that warrant consideration if investors are to be properly protected.

The lack of fundamental valuation metrics makes investment decisions inherently speculative and prone to irrational exuberance. Coupled with characteristic volatility, excessive risk-taking behaviour can lead to large losses [17]. Additionally, regulatory ambiguity, market manipulation and fraudulent activities are pervasive, necessitating robust investor protection measures and regulatory oversight. Investors must note that cryptoassets are not approved under most jurisdictions, meaning protection is limited in the event of losses. One need only to look at the recent collapse of FTX to get a flavour [18].

The UK’s House of Commons Treasury Committee determined that cryptoassets pose significant risks to consumers, given their volatility, with the Chair stating [19]:

The events of 2022 have highlighted the risks posed to consumers by the cryptoasset industry, large parts of which remain a wild west. Effective regulation is clearly needed to protect consumers from harm, as well as to support productive innovation in the UK’s financial services industry. However, with no intrinsic value, huge price volatility and no discernible social good, consumer trading of cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin more closely resembles gambling than a financial service and should be regulated as such. By betting on these unbacked ‘tokens’, consumers should be aware that all their money could be lost.

Harriet Baldwin MP – House of Commons Treasury Committee

Whether investors agree cryptoassets have value or not, regulation certainly lags the risks. Work continues in both the US and UK to implement frameworks for listing standards, focusing so far on regulating crypto-focused businesses, such as Binance and Coinbase, and the implementation of reporting, anti-money laundering (AML) and Know Your Client (KYC) standards [20]. When it comes to the various crypto tokens, Western governments appear nowhere near ready for adoption. SEC chair Gary Gensler hammered home the point:

It [the approval of BTC ETPs] should in no way signal the Commission’s willingness to approve listing standards for crypto asset securities. Nor does the approval signal anything about the Commission’s views as to the status of other crypto assets under the federal securities laws or about the current state of non-compliance of certain crypto asset market participants with the federal securities laws. As I’ve said in the past, and without prejudging any one crypto asset, the vast majority of crypto assets are investment contracts and thus subject to the federal securities laws…While we approved the listing and trading of certain spot bitcoin ETP shares today, we did not approve or endorse bitcoin.

Gary Gensler – Statement on the Approval of Spot Bitcoin Exchange-Traded Products

Regulatory approval of Bitcoin itself is not close. Yet, other cryptoassets exist; assets that retail is involved with daily. The below captures some of the risks that reside with different forms of cryptoassets:

- DeFi Tokens – Digital coins linked to decentralised financial apps, working on distributed networks.

- Smart Contract Risk: code errors on a blockchain can lead to significant losses due to exploitation.

- Regulatory Risk: DeFi operates without intermediaries, making it vulnerable to new regulations that can affect its use, value or legality.

- Rug-Pulls/Exit Scams: likening DeFi projects to Ponzi schemes, anonymously launched DeFi projects increase the risk of developers abandoning projects, leaving investors with worthless tokens.

- Data/Oracle Risk: DeFi relies on external data sources, creating risk of inaccuracies.

- Complexity: it can be challenging for users to understand blockchains and their associated risks.

- Stablecoins – Aim to hold a constant value against fiat currencies or other store of value.

- Counterparty Risk: a backed asset relies on a third party to maintain the collateral. If that party becomes insolvent or fails to maintain the required collateral, the ecosystem is at risk.

- Redemption Risk: the ability to redeem an asset for its underlying collateral may not function as expected, especially during market volatility, and could lead to a run on the stablecoin.

- Collateral Risk: the value of collateral, which may include other cryptoassets, can fluctuate, impacting stability.

- FX Risk: many stablecoins are denominated in US Dollars, exposing global investors to movements in exchange rates against their domestic currency.

- Algorithm Risk: assets relying on algorithms for stability may experience algorithm failure, resulting in a loss of value.

- Meme Coins – Digital coins that increase in value mainly because lots of people online start buying them.

- Volatility Risk: meme coins experience extreme and unpredictable price fluctuations influenced by social media trends, celebrity endorsements and speculative trading.

- Lack of Utility: meme coins often lack intrinsic value and utility, relying on community interest and online trends.

- Market Manipulation: susceptible to e.g., ‘pump-and-dump’ schemes.

- Lack of Transparency: limited information about development teams and financials makes it challenging to assess meme coins accurately.

- Emotional Investing: strong emotional reactions can lead to impulsive decisions, amplifying losses.

- Staked Cryptoassets – Digital tokens locked into a blockchain network to earn rewards.

- Slashing Risk: staking may result in losses if the network penalises a validator for malfeasance.

- Liquidity Risk: Some protocols lock staked assets for specific periods, limiting liquidity.

- APY Not Guaranteed: Staking yields are determined by the protocol and may vary.

- Protocol Risks: Changes or updates to staking protocols can introduce new vulnerabilities or unforeseen outcomes.

- Wrapped Tokens – Digital coins that help cryptoassets work across different networks.

- Smart Contract Risk: vulnerabilities in smart contracts can be exploited, potentially leading to losses.

- Collateral Risk: mechanisms ensuring collateralisation may fail, affecting the value of wrapped tokens.

- Custodial Risk: if the custodian of underlying assets becomes insolvent or experiences fraud or hacking, the value of wrapped tokens may be at risk.

- Pricing Disparity: market inefficiencies or liquidity issues can cause the price of wrapped assets to diverge from their underlying assets.

Closing Remarks

Looking ahead, the future of cryptoasset trading among young investors is likely to be shaped by a confluence of technological advancements, regulatory developments and market dynamics. The launch of ETPs may just be the start of crypto’s integration with traditional finance, but regulatory clarity and institutional involvement are needed, not least to increase confidence and legitimacy in products. Investor protection is paramount, and the right regulation can support safe, broad adoption. Given the exposure retail investors have, the need for proactive legislation is immediate.

[1] The Economist. (2021). Untapped Capital: Understanding the retail investor pool. Available at: eiu-primarybid_untapped_capital_report.pdf (Accessed: 16 May 2023).

[2] The Economist. (2021). Just how mighty are retail traders? Available at: Just how mighty are active retail traders? (economist.com) (Accessed: 5 June 2023).

[3] Perez, G. C., & Suarez, G. R. (2022). Analysis of the behaviour of retail investors in the financial markets during the COVID-19 crisis. Available at: DT_78_Comp_minoristas_COVID_ENen.pdf (cnmv.es) (Accessed: 13 June 2023).

[4] Chatillon, E., et al. (2021). Retail Investors and Their Activity Since the COVID Crisis: Younger, More Numerous and Attracted by New Market Participants. Available at: 20211129-etude-a-publier-vfinale-en.pdf (amf-france.org) (Accessed: 9 May 2023).

[5] United Fintech. (2022). Why now is the time to pay attention to neobrokers. Available at: United Fintech (Accessed: 18 February 2024).

[6] Based on transactions from clients’ checking accounts (5 million) to retail crypto platforms (J P Morgan Chase clients). Wheat, C. & Eckerd, G. (2022). The Dynamics and Demographics of U.S. Household Crypto-Asset Use. Available at: JPMorgan Chase Institute (Accessed: 16 February 2024).

[7] Lammer, D. M., Hanspal, T. & Hackethal, A. (2019). Who are the Bitcoin investors? Evidence from indirect cryptocurrency investments. SAFE Working Paper, No. 277.

[8] Brière, M. (2023). Retail Investors’ Behaviour in the Digital Age: How Digitalisation is Impacting Investment Decisions. Available at: Amundi Research Centre (Accessed: 17 February 2024).

[9] Cornelli, G., Doerr, S., Frost, J., & Gambacorta, L. (2023). Crypto shocks and retail losses. Available at: BIS Bulletin (Accessed: 17 February 2024).

[10] Chainalysis. (2023). The 2023 Global Crypto Adoption Index: Central & Southern Asia Are Leading the Way in Grassroots Crypto Adoption. Available at: Chainalysis (Accessed: 03 March 2024).

[11] Ellsworth, B. (2021). As Venezuela’s economy regresses, crypto fills the gaps. Available at: Reuters (Accessed: 03 March 2024).

[12] IntoTheBlock. Transaction Statistics. Available at: https://app.intotheblock.com/coin/BTC/deep-dive?group=network&chart=transactions (Accessed: 03 March 2024).

[13] Gurrola-Perez, P., Lin, K., & Speth, B. (2022). Retail trading: an analysis of global trends and drivers. Available at: WFE-Retail-Investment Sep 20 2022.pdf (world-exchanges.org) (Accessed: 23 May 2023).

[14] Gensler, G. (2024). Statement on the Approval of Spot Bitcoin Exchange-Traded Products. Available at: SEC.gov | Statement on the Approval of Spot Bitcoin Exchange-Traded Products (Accessed: 17 February 2024).

[15] Pyth Network. (2024). Bitcoin ETF Price Feeds on Pyth Network. Available at: Pyth Network (Accessed: 26 February 2024).

[16] Çabuk, U. C., & Silenzi, M. (2021). Cryptocurrencies in Retail. Available at: CryptoRefills (Accessed: 03 March 2024).

[17] Finance Magnates. (2023). Exploring the Surging Interest of Retail Investors in Cryptocurrency in 2023. Available at: Finance Magnates (Accessed: 03 March 2024).

[18] Reuters. (2022). Rise and fall of crypto exchange FTX. Available at: Rise and fall of crypto exchange FTX | Reuters (Accessed: 18 February 2024).

[19] House of Commons Treasury Committee. (2023). Regulating Crypto. Available at: Regulating Crypto (parliament.uk) (Accessed: 18 February 2024).

[20] George, K. (2024). Cryptocurrency Regulations Around the World. Available at: Investopedia (Accessed: 19 February 2024).