Unlocking Opportunities

The Reprioritisation of Financing

Date of Publication

April 2025

Author

Charlie Kellaway

Reading Time

30 minutes

financing noun

: money that a person or company borrows for a particular purpose, or the process of getting this money or arranging for it to be paid [1]

: the act or process or an instance of raising or providing funds [2]

Introduction

Finance is essential for the evolution of capitalism. It has driven competitive business practice throughout history, evident in industrialisation and the liberalisation of global trade that coincided with financial expansion of the Netherlands and Britain. And today, finance helps businesses and households grow through four key activities [3]. One, it coordinates payment systems for people to purchase goods and for businesses to pay wages. Two, it helps individuals manage their personal finances day-to-day and between generations. Three, finance helps people manage risks associated with everyday economic activities. And four, finance matches asset-rich people with idea-rich people to stimulate the most effective allocation of excess capital [4]. Financing, the fourth activity, is the focus of this essay.

At its core, financing unlocks capital for businesses, supporting enterprise owners to purchase otherwise inaccessible capabilities. It allows entrepreneurs to deploy innovative solutions that use finite economic resources more efficiently and benefits society by helping to make increasingly productive technologies cheaper and more accessible. Perhaps expectedly, then, financing activities are strongly and positively associated with growth of income per capita [5]. Modern societies need it.

However, despite a thriving global financial services industry growing 7.7 percent per annum and clear links between productive financing and economic prosperity, western societies are stalling [6]. Extreme economic inequality has emerged as one of the most significant social problems of our time. In most OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries, the gap between the rich and poor is at its highest level for 30 years, and asset ownership is increasingly concentrated among the wealthiest [7-8]. When income inequality rises, economic growth falls, and these problems are worsening [9].

This harms all our prospects, motivating exploration of why growth has deteriorated. That is the purpose of this essay—to explore the role of finance in stimulating growth, to consider how and why financing activities have detached from growth and to challenge current applications of financial expertise. We argue that the reprioritisation of financiers to place revenues above all else has introduced degrees of volatility that threaten prosperity, with the intention of presenting viable alternatives to current financing solutions that can aid global economic development.

The Business of Financing

There are two broad methods of financing. Each carries advantages and disadvantages, but both capitalise on the fact that some people have surplus money and wish to generate returns, whilst others have ideas to build profitable enterprises but need money to do so. Firstly, business owners may use equity financing, selling stakes in a company to investors for cash. This is advantageous because a business need not pay investors back, since they become part owners and bear the risk of failure. However, founders increasingly lose control as an investor base grows, and it becomes challenging to operate without influence. Alternatively, owners may seek debt financing. Institutions—historically, banks—lend capital at a certain rate and claim no ownership, so founders retain control and may spend borrowed cash to pursue growth. But debt must be repaid, often with interest, increasing expenses and introducing risk for borrowers who must handle incremental changes to their cash flows.

Both methods have been critical for capitalism to thrive. Studies have consistently found external investment to be positively correlated with productivity and business performance, since capital unlocks buying power for innovators who, released from the pressure of balancing cash flows, can focus on building [10-12]. Conversely, restricting capital deployment can dampen growth; for example, if credit is limited, companies may struggle to invest and develop [13-14]. This is important: encouraging innovation and supporting entrepreneurs is largely beneficial, since new companies often stimulate growth and competition. They create jobs, provide income streams, open opportunities for upward social mobility and contribute to economic efficiency—benefits particularly acute in countries struggling to overcome economic stagnation [15]. Societies prosper when finance supports entrepreneurship.

Privately held small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) rely particularly on this process, since well‐funded start‐ups have significantly lower probabilities of discontinuance. From start-ups to partnerships to sole traders, SMEs represent 99% of all businesses in the European Union (EU) and produce most of the economic output in the United States (U.S.) [16-17]. They are also top employers, generating over 60% of new job growth [18]. But SMEs face great uncertainty over their market position and incur outsized operating expenses relative to revenues as they establish themselves. Unsurprisingly, a lack of financial resource is consistently identified as the primary reason for business failure across industries, geographies and periods [19-27]. For example, between 1986-1994, manufacturing firms in Tokyo lacking sufficient capital had a significantly higher risk of failure, and an assessment of 200 small businesses in the Middle East categorised the main causes of failure into financial and managerial factors, concluding that financially astute management should be the top consideration for small business ownership [25-26]. In all, access to finance has been identified by SMEs in many countries as their single largest obstacle that inhibits growth in both size and productivity [27].

Opportunities to raise supportive external capital can, therefore, be transformative. Founders know this: of 150 surveyed, over half believed that running out of money led to their business failing and 47% recommended more financial backing as the preventative [28]. Though not the sole cause of failure, new firms deprived of capital must battle dominant incumbents without appropriate investment into emerging technologies. They also struggle to pivot if an initial product fails. And, critically, macroeconomic volatility can take a severe toll as small firms are less able to withstand drops in revenue amid uncertainty. For SMEs, insufficient financing can be fatal.

Yet, securing capital is not easy. A Bank of England survey of 3,000 SMEs in the United Kingdom (UK) found that one fifth could not access debt finance on reasonable terms. 20% felt they had underinvested in their business, of which 58% cited credit as too expensive, 55% could not borrow at a reasonable rate, 33% lacked suitable collateral to borrow and 29% believed their application would be in vain [29]. In fact, more than two thirds of global SMEs who have applied for external capital report being unsuccessful [30]. Financing SMEs can be tricky; smaller, private businesses produce less data, which introduces information asymmetry between borrower and lender and makes it difficult for financiers to understand operations and trajectory. Furthermore, companies with less predictable revenues find it challenging to meet repayments, so are less attractive to lenders. Capital markets also impose high costs to issue equity and subject firms to corporate governance regimes, which can deter smaller companies from listing publicly [31]. These structural impediments limit the capital SMEs can access relative to larger businesses.

Of course, not all SMEs want or need external capital—an important point that we revisit. Clearly, though, financing is necessary for modern society; correlated positively with successful entrepreneurship, business growth and economic development. Financiers broker allocations of capital to ensure surplus wealth is directed towards the most productive users, which unlocks buying power for new technologies that perform human activities more efficiently than before. Without it, budding enterprises would struggle to disrupt established industries.

However, mounting evidence suggests the efficacy of this process is deteriorating.

The Reprioritisation of Financing

Financing ensures that businesses can access the capital they need and financiers evolved to provide this valuable and lucrative work. Entities like investment banks underwrite and issue new debt and equity in private primary markets and may bring a company public via Initial Public Offering (IPO) on the secondary market. At each stage, banks court investors to support the company’s operations, and a bank grows with success as a financing partner. These mechanics ensure that a financier earns fees for its role and an enterprise has buying power to grow, whilst society benefits from the creation of new jobs and services.

Today, however, large companies are often self-sufficient and finance investments with cash generated from their operations. This has diminished the need for public raises, yet investment banks still encourage large companies to list publicly, attracting swathes of institutional investors to share in their profits. Principally, these include long-term asset managers, who buy and hold companies to gain controlling positions and extract dividends, and short-term trading desks, who buy and sell debt and equity to capture value for a bank’s bottom line. Both divisions operate within the very firms hired to finance the original companies, marking a shift from traditional financing activities.

This trend is easily traced. In the early 1980s, investors were typically active and regional with mid- to long-term mindsets. But the potential for excess returns naturally attracted new players and strategies shifted with the emergence of hedge funds. The search for alpha, like all trade, became global, which led to financiers owning and selling companies in various blends across various time horizons. With time, and as competition intensified, financiers sought to capture smaller alphas over shorter periods. The market reprioritised to focus on secondary trading.

For example, over the last decade, Goldman Sachs’ has derived 70% of annual revenues from investment management and trading, and less than 20% from debt and equity issuance [32]. Between 2018-2024, annual global secondary market trading volumes increased from $74 billion to $162 billion, and the top 14% of banks by assets under management (AUM) and trading volumes have driven this to account for 80% of industry profits [33-34]. So, though the need for primary issuance and financial support on secondary markets has decreased, trading volumes have greatly increased and, with them, bank revenues. But trading is not necessary for non-financial business development. Volatility in stock markets is far greater than can be explained by changes in the fundamental value of securities, and excess trading simply creates noise on which banks can capitalise [35]. Problems emerge because disproportionate revenue growth in the financial sector and pursuit of higher short-term profits both encourage excessive risk-taking (which contributes to bubbles and crashes when market conditions change) and divert resource away from the non-financial economy [36]. Consequently, as financiers reduce issuance and scale alpha-focused activities, value is withdrawn from the system.

This reprioritisation neglects the core business of financing—capital allocation for entrepreneurial growth—and is a pressing issue. Consider that UK businesses derive 80% of their external financing from banks [37]. SMEs have always faced challenges to unlock external finance, but the decline of traditional banking has further increased credit scarcity and even companies with a strong credit history now find it difficult to obtain loans [38]. SMEs increasingly rely on alternatives such as personal networks, use of which has surged 11% since the pandemic, but these options are riskier and less conducive to development [30]. Family contributions, for example, are correlated with reduced appetite for entrepreneurial risk-taking, since the economic status of people close to the founder depends on business continuance [39]. If a business falters, an owner will likely ruin her personal credit or lose savings. And though online loans offer more relaxed qualification requirements than banks, they impose substantially higher interest rates (averaging 6-30% APR versus 7.71-8.89% at traditional banks) [40]. This has degraded the outlook for SMEs; since 2017, the number of small business owners who perceive that they have good current access to capital has declined by one third from 67% to 49% [41]. Options appear increasingly limited.

UK businesses are weaker as a result. Today, approximately 5.5 million private businesses operate in the UK, compared with 31.7 million in the U.S. [42-44]. Of these, the UK counts 53 unicorns (privately held companies with a valuation of $1 billion or higher) cumulatively valued at $176.69 billion [45]. The U.S. holds 656 unicorns valued at $2,111.7 billion. So, the U.S. mints over double the number of unicorns per million companies and does so more efficiently, operating with 10.7 people per company compared to 12.43 in the UK. The U.S. also hosts trillion-dollar public companies, alongside depth and liquidity that far outstrips that in the UK, capitalising on structural issues in Europe to encourage companies and entrepreneurs to head to the U.S. Differing attitudes towards financing in the UK and U.S. have contributed to divergent pathways of business success.

Why? Compared to the UK, the U.S. initially handled the reprioritisation of banking well, tilting public policy in the 1980s towards an entrepreneurial society that intentionally supports young firms lacking access to bank finance [46]. As U.S. banks reduced lending to mid-cap companies, they were replaced by private equity funds (PE), venture capitalists (VCs), angel investors and thousands of regional lenders. Emerging to support SMEs without credit history or collateral, the growth of these entities has been astounding. AUM of VCs swelled from $242 billion to $1.21 trillion between 2010-2023, whilst the number of PE firms increased by 60% between 2016-2021 [47-49]. Today, 18,000 funds hold assets of $4.4 trillion and private funds are the primary providers for U.S. businesses which, in contrast to the UK, depend on traditional banks for just 20% of their capital [50]. Cultural support for entrepreneurial financing has since been found to foster environments that are critical for growth, and the U.S. successfully leveraged this phenomenon to prosper [51].

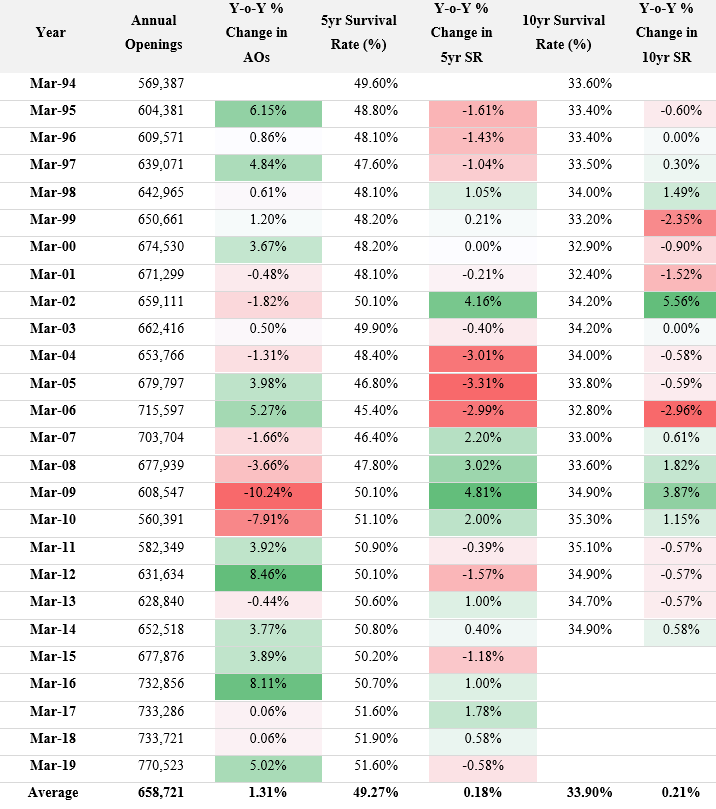

However, data on business survival rates in the U.S. reveal a worrying trend. Since 1994, on average, 49.27% of new firms in the U.S. remain operational after five years, dropping to 33.90% after 10 years (Table 1) [52]. This is not unexpected if we consider that investment bank lending has decreased, and VCs focus on early-stage SMEs. Firms outside of this cohort receive less funding, supporting literature that correlates a lack of capital with discontinuance [19-27]. Nonetheless, though the number of annual openings has increased 35.33% across this period, the expected five-year survival rate has increased just four percent. Moreover, an annual increase or decrease in the number of new firms is met with an opposing effect on survivability in 16 of 25 annual sessions (64%). In other words, for a given year, when the number of new firms increases, the survivability rate will likely decrease, and vice versa. This suggests that, despite a proliferation of private financiers and increasing entrepreneurial activity, current solutions fail to improve the survivability of new businesses.

Though initially designed to support start-ups, the truth is that VCs, like banks, now also prioritise revenues over economic growth [4]. Many VCs have been subsumed into the operations of large banks, whilst private equity has transitioned to buying out existing businesses from large corporations or refinancing established companies with a focus on short-term profits. Rampant merger and acquisition (M&A) activity, combined with shrinking bank appetite to support SME IPOs, contributed to a near 50% fall in the number of public companies in the U.S. between since 1996-2020, to around 3,600 [53]. Termed de-equitisation, this activity has increased the time that companies remain private, allowing PE firms and founders to scale with private capital. Though beneficial for large tech companies (for example, AirBnb remained private for 11 years and opened for trading in 2020 valued at $100.7 billion), this has consequences [54]. Alpha-generating assets are increasingly concentrated among the wealthiest, forcing public investors to turn to passively managed exchange-traded funds (ETFs) focused on the Magnificent 7 and biggest global companies just to keep pace with benchmarks [55]. De-equitisation robs markets of value by cutting SMEs from public portfolios and limiting investor diversity. Similarly, since over 90% of the stocks that disappeared were small- and micro-cap companies, de-equitisation has squeezed out competition to progressively concentrate industries into the hands of large public companies. And since PE firms extract fees, cut jobs and load leverage onto a business to achieve short-term profits, portfolio companies are 10 times more likely to go bankrupt than non-PE-owned companies within 10 years of acquisition, often failing to adequately compete against incumbents [56]. In all, this suggests that PE financing is frequently damaging to both acquired and public businesses and is evidence that private capital has accelerated the narrowed deployment of finance to extract value at the expense of economic growth.

Consequently, America’s entrepreneurial society, too, is faltering, and we conclude that value extraction by financiers is linked to stuttering growth in two of the world’s leading economies. However, knock-on effects are not limited to the U.S. and UK. Policymakers are concerned that the decline in small business lending has hampered global economic recovery since 2008. SMEs employ roughly half of the private sector labour force and average over 40% of private contributions to global gross domestic product (GDP) but underperform if unable to access capital, which slows product development, employment and growth [38]. This has contributed to a series of downward shifts in global growth since 2008-09, from 5.9 percent in the 2000s to 5.1 percent in the 2010s to 3.5 percent in the 2020s [57]. Current projections expect growth to settle at 2.7 percent in 2025-26—insufficient to support sustained economic development.

Moreover, recent, low growth has disproportionally benefited higher income groups, leaving lower income households behind [58]. For example, developing economies began the twenty-first century growing at the fastest rate since the 1970s and now account for nearly half of global GDP, up from 25% in 2000 [57]. However, progress largely occurred prior to the Global Financial Crisis. Since 2014, excluding India and China, growth of the average income per capita in developing economies has been half a percentage point lower than in wealthy economies, widening the rich-poor gap. In addition, private ownership of SME assets, often portrayed as a democratic and accessible “building block of economic opportunity”, is increasingly concentrated among the wealthiest households [59-61]. Since 1989, the top one percent’s share of total wealth has increased by eight percent, dropping to five percent if private business assets are excluded [8]. So, asset concentration is magnifying inequality. The result is a widening gap between rich and poor in most OECD countries at its highest level for 30 years. Since this cohort cannot realise their human capital potential, distancing the lower 40% drags GDP, to the detriment of global economies [7].

The Purpose of Financing

By prioritising revenues, financiers have deprived SMEs of productive financing and neglected economic development. It is, therefore, in our best interest to find solutions that can support SMEs and reignite growth. But to do so first requires thinking critically about why this reprioritisation has taken place.

Financiers may be right to prioritise revenue-focused activities. Financing is a service, not a mandate, and most valuable when skilled expertise and capital is directed to the right business. If an entity cannot raise sufficient equity, or is deemed too high-risk a borrower, market economics dictate that the venture being pursued should not take place [4]. It would certainly be destructive for a financier to provide capital to every SME, since not all services contribute equal value to society. Some ventures must fail. Furthermore, there are genuine impediments to capital provision. Liquidity, the ease with which an asset can be bought or sold without affecting its price, is of fundamental concern for financiers. Investors are often required to finance SMEs with long horizons based on imperfect information yet, once capital is allocated to a private business, it becomes very difficult to liquidate. Financiers recognise that suboptimal structures introduce risks that affect their outcomes, which has likely encouraged a preference for more profitable activities.

It is also prudent to recognise that external capital is not always wanted or needed. In fact, almost 70% of SMEs in the UK would prefer slower growth to having debt [29]. Current structures are suboptimal for SMEs too: cost of capital is high, private markets are fragmented and SMEs struggle with corporate governance requirements and dilution of ownership [31]. When demand for capital drops, financiers must generate revenues by other means and have found trading and asset management to be most profitable. Moreover, business failure is, at times, attributable to funding [62]. Excess capital to pursue weak products or conceal problems will detract from appropriate management of a company, hurting both owners and investors. It is likely, too, that large external shareholders will appoint their own CEO, which can hinder progress. Firms retaining a founder at the helm reliably outperform; an assessment of 2,327 U.S. companies between 1992-2002 found that an investment approach holding 361 companies run by founders would have earned an excess annual return of 10.7%—4.4% more per annum than a portfolio holding all companies (both founder-led and those with an appointed CEO) [63]. This effect holds when controlling for factors such as industry and age of business, has since been replicated, and is also correlated with innovation [64]. Between 1993-2003, founder-led companies produced 31% more significant patents compared to companies under appointed CEOs [65]. It cannot, therefore, be argued that increased capital will always lead to growth, since aimless allocation or misguided management may have a degrading effect. Astute solutions that balance business and financier needs are critical.

However, evidence strongly suggests that financiers have weighted solutions disproportionately to the needs of investors. Contrast the average annual return in private equity—10.48% over the 20-year period ending June 2020—with the 10-fold increase in likelihood of failure of an acquired business [66]. Short-term revenues are clearly prioritised over business health, and it is reductionist to suggest structural impediments are at fault. If low liquidity is an issue, we should not expect 50% of public companies to be taken private. If market structure is an issue, we should reasonably expect lobbying or solutions to impediments. Financiers simply have not sought to overcome these problems with innovative, value-add services.

Public markets were once environments where large pools of fundamental capital drove asset prices over long periods of time. But that has changed, and durations have shrunk materially. Though just half of SMEs remain operational within five years of inception, the global financial services industry grows 7.7 percent per annum by reducing access to capital, pumping volumes, freely deploying leverage and acquiring or shorting assets [6]. Short-term, levered and inverse products drive a lot of daily activity as traders seek small alphas amplified by leverage, encouraging churn. Ultimately, financiers have purposefully scaled activities that prioritise revenues and reduced productive solutions for the non-financial economy.

These behaviours caused widespread disruption during the Global Financial Crisis, after which UK and U.S. banks were bailed out with £137 billion and $700 billion in government funding, respectively, despite their central role in the downturn [67-68]. Public opinion subsequently became sceptic and distrustful, with many going as far as to consider banking a scam. Journalist Matt Taibbi encapsulated this view, denoting financiers as grifters actively seeking to extract value from the system at public expense and categorising the shift in bank priorities as a land grab by the most powerful that is driving economic breakdown [69].

“What has taken place over the last generation is a highly complicated merger of crime and policy, of stealing and government. Far from taking care of the rest of us, financial leaders of America and their political servants have seemingly reached a cynical conclusion that society is not worth saving and have taken on a new mission of absconding with whatever wealth remains in our hollowed-out economy. They don’t feed us—we feed them.”

M. Taibbi, Griftopia, 2011

There is truth in Taibbi’s comments. Financiers clearly prioritise revenues over entrepreneurship and economic growth, and it is right that their trustworthiness be questioned. However, the extent to which bank activity is ‘stealing’ that aims to ‘hollow out’ society is contentious. Taibbi’s critique ignores $321 billion in penalties U.S. banks have paid out since 2008 and disregards any benefits that finance still provides [70]. Some financiers actively support SMEs; between 2014-2023, though the share of lending provided by the top five UK banks decreased from 63% to 41%, 60 new banking licenses were granted, of which 36 served small businesses [71]. Challenger banks collectively surpassed the big five’s market share in 2021. Taibbi ignores such activity, undermining his argument. If stealing was the motive, we would not expect productive efforts by new financiers, so the ‘grift’ fails to adequately explain reprioritisation.

Economist John Kay offers a more nuanced critique, posing that, by focusing on revenues, financiers have replaced strategic knowledge of appropriate debt and equity solutions with expertise in the mechanics of intermediation [4]. Finance should exist to support businesses and create value, and financiers must have deep knowledge of a client’s needs, finances, culture, employees and mission. However, material improvements in services for the non-financial economy are lacking. The industry understands that the largest rewards are earned by those who implement strategies to extract value and is devoted not to the creation of new assets but to the rearrangement of those that already exist. Trading volumes and intermediary revenues have increased, yet primary raises and public listings have decreased. The number of funds and AUM have increased, yet non-financial industries are consolidated. The financial services industry grows 7.7% per annum, yet the survivability of SMEs remains constant. Financier revenues simply have not been met with proportional improvements in expertise. Reprioritisation, therefore, reflects how a focus on revenue has degraded the industry’s ability and willingness to fulfil its purpose.

Kay’s assessment captures the culmination of an economic movement that has guided financiers for decades. In 1970, renowned economist Milton Friedman published his theory, ‘A Friedman Doctrine: The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Profits’ [72]. Friedman argued that the only purpose of a business is to use its resources to engage in activities that maximise revenue and shareholder value, and all else will follow. His argument earned the name ‘shareholder theory’ for stating that owners may conduct a business in accordance with their desires—largely to make as much money as possible while conforming to the basic rules of the society. Shareholder theory has held court for decades, through the decline of bank lending and rise of private equity and was declared “the biggest idea in business” by The Economist as recently as 2016 [73]. It influenced generations of executives to focus on making money above all else and appears heavily intertwined with, if not the key driver of, the reprioritisation from allocation to extraction by financiers.

Many of the world’s current CEOs, Nobel laureates and top thinkers at least partially blame today’s economic inequalities on Friedman’s mandate and the capitalist obsession with fulfilling it [74-75]. Colin Mayer CBE, who spent a decade challenging shareholder value maximisation, admonishes Friedman’s premise as unnatural and encouraging of harmful economic behaviour. Mayer flips shareholder theory on its head, arguing instead that every business owes a responsibility to society to deliver on its purpose [76].

“The assets of a firm have been accumulated on the back of investments of virtually every segment of society—employees, suppliers, communities, nations…Shareholders do not and should not have rights to do with their companies what they please…They have roles and responsibilities as well as rights and rewards deriving from their dependence on and obligations to the societies in which they operate…

Instead, the corporation should be recognized for what it is—a rich mosaic of different purposes and values. It exists to…fulfil its purpose…Everyone else—shareholders, executives, employees, and suppliers—are there to help it do that. The corporation is an employer, investor, consumer, producer and supplier all rolled into one. It uses capital, labour, land, materials and nature in varying proportions…in other words it is a user of a range of inputs to produce an even greater array of outputs.”

C. Mayer CBE, Prosperity, 2018

Finance, deeply intertwined with entrepreneurship, growth and development, should exist to serve businesses and customers; to match asset-rich people with idea-rich people and stimulate the most effective allocation of excess capital. Instead, corporations have been encouraged to prioritise shareholder value above all else, and financiers have capitalised on their advantageous position as intermediaries with remarkable efficiency. By prioritising trading and accumulation to surge revenues, financiers have flaunted their obligation to act in society’s best interest and profited at its expense. Failure to fulfil a meaningful purpose has eroded the principles that drive economic prosperity and contributed to the most severe inequality and stagnant growth for 30 years.

The Decentralisation of Financing

Western societies are now wilting under the strain of excessive, yet, narrowed, enrichment. We face a dilemma: how to limit revenue-seeking behaviours—those which contribute to increasingly dangerous volatility and inequality—without undermining the ability of finance to play its essential role in global capitalism [77]. Heavy-handed solutions to prevent or over-regulate current activities risk displacing expertise if financiers abandon markets in search of leniency, which would be detrimental. Instead, we must incentivise collective endeavour, suppressing the focus on individual desires to work for more even distribution. Knowing that SMEs stimulate growth, particularly in countries facing economic stagnation, we conclude that solutions to reform debt and equity financing are vital to this goal [15].

This is achievable, if we leverage the array of powerful technologies available. It is somewhat contradictory that financiers have, historically, supported innovation across every non-financial industry, yet when it comes to models of debt and equity financing little innovation has been applied. Technology can change this, and we must use it to reform capital allocation and restimulate economies.

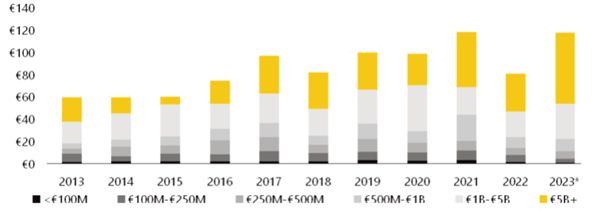

Reconsider the problems in financial markets. Entities face high costs at issuance; intermediaries dictate credit scores and interest rates; information asymmetries prevent many SMEs from securing credit; non-bank sources of financing impose greater risks on business owners; industries consolidate as smaller companies are privatised; opaque reporting mechanisms reveal little about private investors or their control; investors struggle to liquidate interests in private companies, disincentivising allocation to riskier SMEs; and secondary markets for interests in VC or PE funds are inefficient, lack visibility and are generally accessible only to investors who meet stringent requirements. Structural constraints have both enabled and driven financiers to prioritise short-term activities, harming businesses, consolidating ownership and increasing inequality. Moreover, rather ironically, these issues are beginning to affect financiers. For example, due diligence is vital to successful financing but increasingly arduous. M&A analysts spend 64% more time on due diligence today than in 2013, pouring over processes, procedures, valuation guidelines, co-investment policies, financial reports and projections, and data stored in virtual data rooms (online repositories for confidential documents) have swelled, increasing 69% between 2018-22 [78]. Cross-border M&A, which accounts for 35% of all mid-market deals (€10-200 million), introduces tax, regulatory and linguistic complexities, alongside macroeconomic risks [79]. Therefore, high quality due diligence (and the ability to prepare detailed, customised proposals) is a major challenge, and done poorly can be fatal, with some firms reporting as few as 10% of deals completing [80]. This affects smaller funds, which are struggling to handle the progressively laborious, manual analytical strain and accompanying investment in people and infrastructure. As a result, LPs increasingly prefer larger, more established players, and PE funds over $1 billion now represent nearly 82% of all capital raised in Europe (Figure 1) [81-83]. Capital is consolidating to the biggest managers as barriers to entry leave small players behind.

However, these many of these structural problems are rooted in centralised control, competition and an unwillingness to share information. They may be resolved by solutions that incentivise more open and productive financing, which brings decentralised technologies into play.

Decentralisation took off when bitcoin (BTC)—a cryptocurrency for electronic payments on the Bitcoin Network—became one of the top 10 most valuable assets globally just a few years after launch [84]. But the real innovation was the underlying infrastructure. Bitcoin was the first tangible example of blockchain: a subset of distributed ledger technology defined as a decentralised, peer-to-peer network for transactions based on cryptographic proof [85]. Blockchain records transactions like a typical ledger but distributes digital records across all network participants to give everyone an updated copy after an event. Each block is a package of validated transaction data cryptographically secured to the preceding block, creating an immutable chain of records that ensures anyone can authenticate ownership at any time [86]. Each network user, or node, may keep their private information secret whilst displaying a public address so that others know they are transacting with a legitimate entity. Moreover, blockchain uses coded programs called smart contracts to automate the exchange of information and assets between two users based on preset conditions [87]. The resulting technology enables any two willing actors to transact directly, securely and efficiently, without oversight from a trusted financial intermediary and without needing to know each other’s identity, preventing a central party from gaining outsized control of a system.

Decentralised trade works because blockchains use consensus mechanisms to validate transactional events. Though different mechanisms apply different underlying dynamics (consider Proof-of-Work versus Proof-of-Stake), all models allow any approved individual to help validate transactions from anywhere in the world. This enables blockchain to coordinate complex behaviours without central control—a relatively common phenomenon in nature. For example, as observed in Lindauer’s Eck Swarm, bees coordinate with precision to find a new hive, despite a complete lack of any apparent means of centralised management [88]. Instead, the swarm compounds behaviour across thousands of individual organisms to vote on the best option. Blockchain, at core, is simply a technology to unlock this natural phenomenon of collective endeavour in humans. And, if we can successfully apply it within business contexts, we may potentially transform a range of financial activities—debt and equity issuance included.

For example, blockchain can help financiers and businesses overcome operational challenges. Using networks to distribute immutable, secure and real-time records across funds and syndicates would allow financiers to audit businesses in real-time, quickly alleviating asymmetries on a grand scale. Consider that, following an operational change or product launch, an SME could use blockchain to update all financiers privy to their profile. This promises a remarkably efficient way for SMEs to create a network of suitable investors and for financiers to map prospectives. Moreover, financiers could securely share due diligence between themselves. Even in a competitive M&A landscape, funds would benefit knowing that another firm has run due diligence and rectified inaccuracies in a prospect’s accounts, which should a) speed up due diligence, b) speed up syndication and c) incentivise data accuracy. Equally, owners may be more comfortable uploading statements, projections and plans to a secure blockchain as they could vet and approve financiers before allowing them access and audit and revoke access at any time. The resulting reduction of information asymmetries should improve financier confidence ahead of allocation and increase access to capital for SMEs.

Another promising feature of blockchain is tokenisation: the act of representing real-world assets (RWAs) as digital tokens to improve capital efficiency. Tokenisation involves first immobilising a physical asset in a controlled location (such as with a qualified custodian), then digitally representing the asset on a blockchain [89]. The digital token is coded to behave in line with preset rules (known as embedded functionality), such as tracking a physical index or calculating an interest payment. This is potentially transformative because tokens behave like physical assets but are divisible into fractional shares, allowing investors to partake at lower thresholds. Fractionalisation has been successfully applied in equity markets: neo-brokers like Robinhood and eToro have digitised their offerings to make equities more accessible for younger retail investors. In fact, the growth of a digital-native investors, driven by fractionalisation, digitisation, gamification and meme mania is one of the most prominent trends in capital markets. 70% of millennials prefer digital platforms and tools to human advice when forming their strategies, compared with just 30% of those 65 or older, and this cohort is rapidly entering markets [90-91]. The value of client assets held by neo-brokers in the EU has increased from €20 billion in 2019 to over €150 billion today, and the depth of retail participation has a positive impact on liquidity, momentum, vibrancy and health of a local market [92-93]. Tokenisation can capitalise on, accelerate and differentiate this trend by lowering investment minimums in illiquid or restricted classes to diversify investors and stimulate new markets [94].

Entrepreneurs have already tokenised tangible assets, like real estate and commodities, financial instruments, like equities and funds, and intangible assets, like digital art and intellectual property. Large investments in a hotel can be fractionalised, making it feasible for property businesses to engage smaller, more diverse financiers. And representing private stock as tokens would support SMEs by a) enabling more investors to partake in financing rounds, b) allowing family and friends to exit their positions, and c) improving price formation to lower the costs of issuance. In all, increasing capital availability and liquidity in private markets would alleviate many of the structural inefficiencies that hinder SMEs. But tokenisation also supports financiers, appearing particularly relevant for private equity. PE is restricted by high investment minimums due to illiquidity, with Limited Partners (LPs) typically locked in a fund for seven years [95]. LPs increasingly desire the ability to rebalance or exit a position, and the PE secondaries market, which supports the purchase and sale of existing stakes in funds or PE-backed companies, is one of the fastest growing subcategories in private equity, from $2 billion in 2002 to $40 billion in 2015 to $152 billion in 2024 [81, 96]. Tokenising funds would allow LPs to sell part of or all their stakes by fractionalising interests into smaller, digital formats, making partial ownership and lower minimums a reality and opening doors to investors with capital or geographical disadvantages. Moreover, liquid secondary markets for PE interests may discourage short-termism since, if LPs could exit anytime, there should be less pressure to deliver outsized returns within the seven-year period. For SMEs, this could translate to more conscientious management under PE ownership and mark a return to the benefits of this financing model.

Blockchain also uses smart contracts to automate allocation. Debt and equity issuance incur high costs in traditional markets due to the involvement of, and fees for, intermediaries, and debt financing is particularly labour-intensive due to administrative burdens on both lender and borrower. However, logging investments, staff, operations and credit history on a blockchain would create efficiencies. Firstly, lenders should be more comfortable providing capital if transparent, real-time data confirms that an SME meets certain conditions, and they can code smart contracts to automatically issue capital if those conditions are met (for example, if an SME passes a risk assessment). In addition, embedding operations to stagger issuance, calculate interest rates or cancel financing rounds based on current market conditions would both protect investors and personalise solutions for SMEs in real-time. Smart contracts also settle transactions in minutes, in contrast to T+1 to one week in traditional markets, improving liquidity in primary and secondary environments. Cumulatively, these features reduce operational costs which, as shown by 50% fee reductions on blockchain-based lender Figure Technologies, should translate into lower costs for both investors and owners [97].

There are, of course, challenges. Blockchain is an emerging, frontier technology, subject to technological and regulatory constraints. Regulated financiers use a variety of systems to run their operations, underpinning everything from calculating a borrower’s credit score to trading securities intraday, and these systems are vital to market integrity, since outages compromise the orderly functioning of markets, deprive consumers of access to financial services and undermine faith in the sector [98]. Regulators, therefore, require that IT and cyber arrangements are proportionate to the nature, scale and complexity of an institution and are sufficiently robust to ensure the continued availability and security of key services. However, blockchains do not currently meet the scalability standards required of traditional financial infrastructures. Observed in the Blockchain Trilemma, which states that optimising one of three critical aspects of blockchain (decentralisation, scalability and security) likely compromises the others, this limitation is cause for concern [99]. If we intend to decentralise millions of transactions across thousands of participants and all manner of assets, we must increase scalability and retain security, else blockchain cannot become essential infrastructure [100]. The risk of outages and disruptions would be too great.

We must also consider competition concerns. Opportunities for diversification also present risks; assets in line for tokenisation are illiquid and challenging to value for a reason and it is likely that institutions will create new distribution channels for assets they cannot easily offload elsewhere [101]. Proper regulation, disclosures and investor protections must prevent institutions from transferring illiquidity risk to retail under the guise of innovation. Yet, equally, permissioning access to networks that facilitate debt and equity issuance will cut certain investors and SMEs out of a chain or class. Though at times prudent, noting consumer protection laws, it is difficult to argue that this would not resemble the current financing landscape. Blockchain is set to democratise value creation, but excessive restrictions may again centralise ideation and wealth. So, regulations will be critical to ensure that innovation and safety are suitably balanced.

Similarly, given the scarcity of qualified developers and expertise, blockchain deployment is expensive and time-consuming, which may prevent smaller financiers from modernising their systems and exclude them from the ecosystem. It will also require significant work to ensure that data on one blockchain can be exchanged or used across another since, in their natural state, distinct networks cannot converse. Without interoperable solutions, tokens would be isolated on one chain which a) may introduce complexity for both SMEs and investors and b) introduces the risk of monopolisation should one network accrue significant value. As Alexander Karp, co-founder and CEO of Palantir Technologies Inc., poses, when emerging technologies which give rise to wealth do not advance the broader public interest, unrest frequently follows [102].

“The decadence of a culture or civilisation, and indeed its ruling class, will be forgiven only if that culture is capable of delivering economic growth and security for the public…[yet] far too much capital, intellectual or otherwise, has been dedicated to sating the often capricious and passing needs of late capitalism’s hordes”

A. Karp, 2025

This statement appears also to describe the current deployment of traditional financial technologies. The world contains hundreds of thousands of financial organisations, from multi-billion-dollar banks down to individual advisors. But they are collectively failing to innovate in the way society needs, and stagnant growth is a consequence.

Blockchain must not follow the same path. It empowers individuals to contribute value to a shared culture and promises to overcome many of the structural impediments afflicting financial markets. New standards that challenge centralised models can allocate capital more effectively; smart contracts that respond in real-time can automate and personalise issuance, lending and settlement; increased liquidity should diversify expertise and capital; immutable records should allow investors, owners, regulators and auditors to map existing interests; and digital networks would allow information transfer across broad yet secure networks. Equally, for financiers, transparency would aid reporting and portfolio management; smart contracts can improve the efficiency of issuance; secure, digital storage should enhance due diligence; tokenisation should attract more capital; and increased liquidity may reduce the downside risk of investing in SMEs. The combination of security, tokenisation and automation promises to transform financing.

It is not perfect, but it is worth the risk. The point of innovation is to push the boundaries of possibility—to support human activity in ways more wonderful and powerful than before. Contrasting Friedman, the responsibility of business must be to engage in activities designed to create value for society and for the future. Financiers once understood this, but they have since reprioritised. What we need now are projects that revolutionise financing and technologies that unlock the potential hidden amongst businesses, investors and individuals. For this collective endeavour, blockchain might just be the solution.

[1] O’Shea, S. (2011). Cambridge Business English Dictionary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[2] “Financing.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster. Accessed: 13 February 2025.

[3] Panitch, L. and Gindin, S. (2021). Power and Inequality. 2nd Edition. New York: Routledge.

[4] Kay, J. (2015). Other People’s Money. New York, NY: Public Affairs.

[5] Levine, R. (2005). ‘Chapter 12 Finance and Growth: Theory and Evidence’, Handbook of Economic Growth, 1(A), pp.865-934.

[6] The Business Research Company (2024). Financial Services Global Market Report 2024. Available at: Research and Markets (Accessed: 02 March 2025).

[7] Cingano, F. (2014). Trends in Income Inequality and its Impact on Economic Growth. OECD Social, Employment, and Migration Working Papers. No. 163.Paris: OECD Publishing.

[8] Pernell, K., and Wodtke, G.T. (2024). ‘The distribution of privately held business assets in the United States’, Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 94, 100993.

[9] OECD (2015). In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available at: OECD (Accessed: 05 March 2025).

[10] Bunn, P., Oikonomou, M., Anayi, L., Mizen, P., Thwaites, G., and Bloom, N. (2021). Influences on investment by UK businesses: evidence from the Decision Maker Panel. Available at: Bank of England (Accessed: 05 March 2025).

[11] Frimpong, F.A., Akwaa-Sekyi, E.K., Sackey, F.G., and Solé, R.S. (2022). ‘Venture capital as innovative source of financing equity capital after the financial crisis in Spain’, Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2087463.

[12] Sahasranamam, S., Lall, S., Nicolopoulou, K., and Shaw, E. (2024). ‘Founding Team Entrepreneurial Experience, External Financing and Social Enterprise Performance’, British Journal of Management, 35, 519-536.

[13] Dalio, R. (2022). Principles For Navigating Big Debt Crises. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster Ltd.

[14] Fraser, S., Bhaumik, S.K., and Wright, M. (2015). ‘What do we know about entrepreneurial finance and its relationship with growth?’, International Small Business Journal, 33(1), 70-88.

[15] Chan, J. and Fung, H. (2016). ‘Rebalancing Competition Policy to Stimulate Innovation and Sustain Growth’, Asian Journal of Law and Economics, 8(1).

[16] European Union (2003). Commission Recommendation of 6 May 2003 concerning the definition of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (Text with EEA relevance) (notified under document number C(2003) 1422). Luxembourg: Official Journal L 124, 20/05/2003 P. 0036 – 0041.

[17] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2025). Business Employment Dynamics. Available at: BLS (Accessed: 26 February 2025).

[18] Hutton, G. (2024). ‘Business Statistics’, House of Commons Library. Available at: Research Briefings (Accessed: 28 February 2025).

[19] Arasti, Z. (2011). ‘An empirical study on the causes of business failure in Iranian context’, African Journal of Business Management, 5(17), pp.7488-7498.

[20] Gaskill, L.R., Van Auken, H.E. and Manning, R.A. (1993). ‘A Factor Analytic Study of the Perceived Causes of Small Business Failure’, Journal of Small Business Management, 31, pp.18-31.

[21] Everett, J. and Watson, J. (1998). ‘Small Business Failure and External Risk Factors’, Small Business Economics, 11, pp.371-390.

[22] Ooghe, H. and De Prijcker, S. (2008). ‘Failure processes and causes of company bankruptcy: a typology’, Management Decision, 46(2), pp.223-242.

[23] Wu, W. (2010). ‘Beyond Business Failure Prediction’, Expert Systems with Applications, 37, pp.2371-2376.

[24] Liao, J., Welch, H. and Moutray, C. (2008). ‘Start-Up Resources and Entrepreneurial Discontinuance: The Case of Nascent Entrepreneurs’, Journal of Small Business Strategies, 19(2), pp.1-15.

[25] Honjo, Y. (2000). ‘Business failure of new firms: an empirical analysis using a multiplicative hazards model’, International Journal of Industrial Organization, 18(4), pp.557-574.

[26] Al-Shaikh, F.N. (1998). ‘Factors for small business failure in developing countries’, Advances in Competitiveness Research, 6(1), pp.75-86.

[27] Ayres, S., and Carter, P. (2024). How and why we finance SMEs. Available at: British International Investment (Accessed: 18 May 2025).

[28] Santoro, P. (2023). Why Startups Fail | Lessons From 150 Founders. Available at: Wilbur Labs (Accessed: 05 February 2025).

[29] Bora, N., Cottell, M., Karmakar, S., King, B., Nyamushonongora, K., and Sengul, S. (2024). Identifying barriers to productive investment and external finance: a survey of UK SMEs. Available at: Bank of England (Accessed: 05 March 2025).

[30] Mambu Communications (2022). Two thirds of SMEs unable to secure funding due to limited access and choice in business lending. Available at: Mambu (Accessed: 05 April 2025)..

[31] Sommer, C. (2024). ‘Can Capital Markets Be Harnessed for the Financing of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs) in Low- and Middle-Income Countries?’, IDOS Policy Brief, 28, EconStor.

[32] Goldman Sachs (2024). ‘2023 Annual Report’. Available at: 2023 Annual Report | Goldman Sachs (Accessed: 13 February 2025).

[33] Private Capital Advisory. (2025). Global Secondary Market Review. Available at: Jefferies (Accessed: 26 February 2025).

[34] Mehta, A., Thomas, K., Dallerup, K., Pancaldi, L., Dietz, M., Patiath, P., Laszlo, V., and Sohoni, V. (2024). Global Banking Annual Review 2024: Attaining escape velocity. Available at: McKinsey & Company (Accessed: 28 February 2025).

[35] Shiller, R.J. (1981). ‘Do Stock Prices Move Too Much to be Justified by Subsequent Changes in Dividends?’, The American Economic Review, 71(3), 421-436.

[36] Cecchetti, S.G., and Kharroubi, E. (2015). ‘Why does financial sector growth crowd out real economic growth?’, BIS Working Papers, No. 490.

[37] Institute of Economic Affairs. (2025). The Real Reason UK Growth Collapsed After 2008 with Tyler Goodspeed. [Online video]. Available at: YouTube (Accessed: 23 January 2025).

[38] Wiersch, A.M., and Shane, S. (2013). ‘Why small business lending isn’t what it used to be.’, Economic Commentary: Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, 10 Aug.

[39] Lardon, A., Deloof, M. and Jorissen, A. (2017). ‘Outside CEOs, board control and the financing policy of small privately held family firms’, Journal of Family Business Strategy, 8(1), pp.29-41.

[40] Sigerson, T. (2024). Online Business Loans vs Bank Loans: A Comprehensive Guide for Small Businesses. Available at: New Frontier (Accessed: 11 February 2025).

[41] Clearly Payments (2024). The Number of Businesses in the USA and Statistics for 2024. Available at: Clearly Payments (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

[42] Number of private sector businesses in the UK 2000-2024. (2024). Statista. [Database]. Available at: Statista (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

[43] U.S. Chamber of Commerce (2023). The State of Small Business Now. Available at: U.S. Chamber of Commerce (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

[44] Office of Advocacy (2023). Frequently Asked Questions About Small Business, 2023. Available at: U.S. Small Business Administration (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

[45] Unicorns by Country 2024. (2024). World Population Review. [Database]. Available at: World Population Review (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

[46] Hechavarria, D.M. and Ingram, A. (2014). ‘A Review of the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem and the Entrepreneurial Society in the United States: An Exploration with the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Dataset’, Journal of Business & Entrepreneurship, 26(1), pp.1-224.

[47] Franklin, B. (2024). NVCA 2024 Yearbook. Available at: NVCA (Accessed: 26 February 2025).

[48] Gensler, G. (2021). ‘Testimony Before the Subcommittee on Financial Services and General Government, U.S. House Appropriations Committee’. Available at: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (Accessed: 26 February 2025).

[49] Sonti, S. (2021). Lifting the Curtain on Private Equity. Available at: aft (Accessed: 26 February 2025).

[50] Mills, L. (2025). Interview: M&G Investments’ big bet on private markets. Available at: IPE (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

[51] Chowdhury, R.H., and Maung, M. (2020). ‘Accessibility to external finance and entrepreneurship: A cross-country analysis from the informal institutional perspective’, Journal of Small Business Management, 60(3), 668-703.

[52] Survival of private sector establishments by opening year. (2024). BLS. [Database]. Available at: BLS (Accessed: 12 February 2025).

[53] Mauboussin, M.J., and Callahan, D. (2020). Public to Private Equity in the United States: A Long-Term Look. Available at: Morgan Stanley (Accessed: 05 March 2025).

[54] Hussain, N.Z., and Franklin, J. (2020). Airbnb valuation surges past $100 billion in biggest U.S. IPO of 2020. Available at: Reuters (Accessed: 22 April 2025).

[55] Most popular ETFs. (2025). Barclays. [Database]. Available at: Barclays (Accessed: 22 April 2025).

[56] Ho, A., and Wong, J. (2024). Private Equity: In Essence, Plunder? Available at: CFA Institute (Accessed: 28 February 2025).

[57] World Bank Group (2025). Global Economic Prospects: Emerging and Developing Economies in the 21st Century. Available at: World Bank (Accessed: 21 March 2025).

[58] OECD (2015). In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All. Paris: OECD Publishing. Available at: OECD.

[59] Yellen, J. (2016). ‘Perspectives on Inequality and Opportunity from the Survey of Consumer Finances’, The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(2), 44-59.

[60] Harrington, B. (2016). Capital without Borders: Wealth Managers and the One Percent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[61] Soener, M., and Nau, M. (2019). ‘Citadels of privilege: the rise of LLCs, LPs and the perpetuation of elite power in America’, Economy and Society, 48(3) 399-425.

[62] Nobel, C., and Ghosh, S. (2011). Why Companies Fail—and How Their Founders Can Bounce Back. Available at: Harvard Business School (Accessed: 13 February 2025).

[63] Fahlenbrach, R. (2009). ‘Founder-CEOs, Investment Decisions, and Stock Market Performance’, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 44(2), 439-466.

[64] Zook, C. (2016). Founder-Led Companies Outperform the Rest—Here’s Why. Available at: Harvard Business Review (Accessed: 01 April 2025).

[65] Lee, J.M, Kim, J., and Bae, J. (2016). Founder CEOs and Innovation: Evidence from S&P 500 Firms. Available at: SSRN (Accessed: 01 April 2025).

[66] Cambridge Associates (2020). U.S. Private Equity Benchmarks (Legacy Definition) Q2 2020 Final Report. Available at: Cambridge Associates (Accessed: 21 March 2025).

[67] Mor, F. (2018). ‘Bank rescues of 2007-09: outcomes and cost’, House of Commons Library, Briefing Paper No. 5748.

[68] Peydró, J.L., Akin, O., and Fons-Rosen, C. (2021). Government-connected bankers made unusually large gains during the 2008 financial crisis.Available at: Imperial College Business School (Accessed: 05 March 2025).

[69] Taibbi, M. (2011). Griftopia. New York, NY: Random House.

[70] Grasshoff, G., Mogul, Z., Pfuhler, T., Gittfried, N., Wiegand, C., Bohn, A., and Vonhoff, V. (2017). Global Risk 2017: Staying the Course in Banking. Available at: BCG (Accessed: 07 March 2025).

[71] British Business Bank plc (2024). Small Business Finance Markets 2023/24. Available at: British Bank Business (Accessed: 05 March 2025).

[72] Friedman, M. (1970). A Friedman doctrine‐- The Social Responsibility of Business Is to Increase Its Profits. Available at: The New York Times (Accessed: 06 February 2025).

[73] The Beautiful Truth Group (2021). What is the Friedman Doctrine? Available at: The Beautiful Truth (Accessed: 24 February 2025).

[74] The Beautiful Truth Group (2020). Greed is good. Except when it’s bad. Available at: The Beautiful Truth (Accessed: 27 February 2025).

[75] Posner, E. (2019). Milton Friedman Was Wrong. Available at: The Atlantic (Accessed: 27 February 2025).

[76] Mayer, C. (2018). Prosperity: Better Business Makes the Greater Good. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[77] Panitch, L., and Gindin, S. (2021). ‘The Making of Global Capitalism’, in Chorbajain, L. (ed.) Power and Inequality. New York, NY: Routledge.

[78] SS&C Intralinks (2024). The Dynamics of Due Diligence. Available at: Intralinks (Accessed: 23 March 2025).

[79] Craninx, P. (2024). The New Shape of Cross-border M&A. Available at: Moore Global Corporate Finance (Accessed: 30 November 2024).

[80] Johnson, G., Whittington, R., Scholes, K., Angwin, D., & Regner, P. (2014). Exploring Strategy: Text and Cases. New York, NY: Pearson.

[81] Zeisberger, C., Prahl, M., and White, B. (2017). Mastering Private Equity. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley.

[82] Capolaghi, L. (2024). Big gets bigger: How consolidation is reshaping Private Equity? Available at: EY (Accessed: 30 April 2025).

[83] Moura, N. (2024). European PE Breakdown. Available at: PitchBook (Accessed: 30 April 2025).

[84] Top Assets by Market Cap. (2025). Companies Market Cap. [Database]. Available at: Companies Market Cap (Accessed: 19 March 2025).

[85] Nakamoto, S. (2008). Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. Available at: bitcoin.org (Accessed: 27 February 2025).

[86] Lacity, M., and Maloney, K. (2017). ‘Blockchain for Business Technical Report: Leading Enterprises to the Blockchain Promised Land’, MIT Center for Information Systems Research.

[87] Szabo, N. (1994). Smart Contracts. Available at: UVA (Accessed: 06 March 2025).

[88] Lindauer, M. (1955). ‘House-Hunting by Honey Bee Swarms’. Translated by P. Kirk Vischer, Karin Behrens, and Susanne Kuehnholz. Journal of Comparative Psychology, 37.

[89] Banerjee, A., et al. (2023). Tokenization: A digital-asset déjà vu. Available at: McKinsey (Accessed: 04 February 2025).

[90] Preece, R., Munson, R., Urwin, R., Vinelli, A., Cao, L., and Doyle, J. (2023). Future State of the Investment Industry. Available at: CFA Institute (Accessed: 04 February 2025).

[91] CFA Institute (2022). Enhancing Investors’ Trust: 2022 CFA Institute Investor Trust Study. Available at: CFA Institute (Accessed: 04 March 2024).

[92] Colesnic, E., Harris, A., and Lorusso, V. (2024). Neo-brokers in the EU: Developments, benefits and risks. ESMA TRV Risk Analysis.

[93] Mijs, W., Koller, M., and van de Werve, T. (2024). ‘Charting the Course: Unlocking Retail participation in EU Capital Markets’, Discussion Paper presented at the European Commission Roundtable on the distribution of retail investment products of 11 April 2024.

[94] Soni, U., Fines, O., and Sun, J. (2025). An Investment Perspective on Tokenization. Available at: CFA Institute (Accessed: 04 February 2025).

[95] Vidal, K.A., and Sabater, A. (2023). Private equity buyout funds show longest holding periods in 2 decades. Available at: S&P Global (Accessed: 24 March 2025).

[96] Green, H. (2025). Lazard 2024 Secondary Market Report. Available at: Lazard (Accessed: 23 April 2025).

[97] Zanev, L. (2025). Debt 2.0: How Blockchain is Making Capital Markets Smarter. Available at: LinkedIn (Accessed: 12 April 2025).

[98] Bauer, M. (2017). Discussion Paper on distributed ledger technology. Available at: FCA (Accessed: 23 April 2025).

[99] Nakai, T., Sakurai, A., Hironaka, S., and Shudo, K. (2023). ‘The Blockchain Trilemma Described by a Formula’, 2023 IEEE International Conference on Blockchain (Blockchain).

[100] Staples, M., Chen, S., Falamaki, S., Ponomarev, A., Rimba, P., Tran, A. B., Weber, I., Xu, X., and Zhu, J. (2017). ‘Risks and opportunities for systems using blockchain and smart contracts’, Data61 (CSIRO), Sydney.

[101] Khan, A. (2025). Why Private Equity Is Betting On Tokenization. Available at: Forbes (Accessed: 09 May 2025).

[102] Karp, A.C., and Zamiska, N.W. (2025). The Technological Republic. London: Penguin Random House.